에 vs 에서 vs (으)로

The differences between of 에, 에서 and (으)로

⭐ 1. “에” — location or destination (at / in / to)

This particle mainly expresses existence at a place or arrival at a destination.

Think of it as a point — like marking a dot on a map.

✔ Basic meaning

Where something is located

Where someone goes (arrival)

⚠ It does not describe the action happening inside the place.

👉 Rough English equivalents: at, in, to

✔ Korean examples

새가 나무 위에 있어요.

→ The bird is on the tree.

☑ 저는 서울에 살아요.

→ I live in Seoul.

★Just one exception: The verb살다 can be used with 에/에서 both. (When the nuance highlights WHERE to live, “에서” used more for it.)

저는 오늘 미용실에 갔어요.

→ I went to the hair salon today.

저는 집에 방금 도착했어요.

→ I just arrived at home.

고아원에 책을 기부를 했어요.

→ I donated books to the orphanage.

👉 Learners can imagine:

“에 = being there or reaching there.”

⭐ 2. “에서” — place where an action happens (at / in)

This particle indicates the stage or background where an action takes place.

Imagine a movie stage where the activity is performed.

✔ Usage rules

Used with action verbs.

Not used with pure movement verbs such as go, come, leave.

👉 Rough English equivalents: at, in depending on context.

👉 Easy idea:

“에서 = where something is happening.”

✔ Korean examples

저는 집에서 일해요.

→ I work from home.

저는 수영장에서 수영했어요

→ I swam in the pool today.

☑ 그 C.E.O.는 비버리힐즈에서 살아요.

→ The C.E.O. lives in Beverly Hills.

▶ There's a nuance that slightly emphasizes where the C.E.O. lives is "Beverly Hills."

그 C.E.O.가 사는 곳이 “비버리힐즈”임을 강조하는 뉘앙스가 있음.

카페에서 두쫀쿠를 먹었어요.

→ I ate Dubai chewy cookies in the cafe.

공연장에서 하루종일 남편과 남동생이랑 연습했어요.

→ I practiced at the concert hall with my husband and my younger brother all day.

창가에서 책을 읽어요.

→ I read books by the window.

⚠ Important contrast:

카페에 갔어요 (I went to a cafe → destination)

카페에서 공부했어요 (I worked at a cafe → action location)

⭐ 3. “(으)로” — direction, route, or means (toward / by / via)

This particle expresses movement direction or method.

Think of it as an arrow showing a path.

✔ Direction (toward)

Used when moving toward a place.

Similar to English toward or sometimes to.

👉The rule:

The noun ending in Vowel + 로

The noun ending in Consonant + 으로

✔ Korean examples

3시까지 회의실로 가야 해요.

→ I have to go toward the meeting room by 3pm.

1년 뒤에 한국으로 돌아가요.

→ I'm gonna go back to Korea in a year.

내일 LA로 출발해요.

→ I depart toward LA, tomorrow.

강아지가 정원으로 뛰어 갔어요.

→ The puppy ran to the garden.

고양이가 위로 점프했어요.

→ The cat jumped (toward) up.

👉 “(으)로 = route or road”

✔ Means or method (by / with / via)

Used to express how something is done.

English equivalents can be:

by bus

in Korean

by hand

via email

✔ Korean examples

약속 장소에 택시로 갔어요.

→ I went to the appointment place by taxi.

같이 한국어로 말해요.

→ Let’s speak in Korean.

오늘 점심은 토마토로 만들었어요.

→ As for today’s lunch, I cooked it with tomatoes.

파일을 왓츠앱으로 보내 주세요.

→ Please send the file via Whatsapp.

운동으로 하루를 시작해요.

→ I start a day with exercising.

⭐ Super simple learner memory trick

에 → “I am there. / I go (toward) there.”

에서 → “I do something ”there”.”

(으)로 → “I move toward or use something.”

☑ Just one exception : the verb 살다 can be used with 에, 에서 both!

Feel & Sense

Let’s learn about expressions about “Feel & Sense” in Korean !

1️⃣ 느낌 (neukkim) — “feeling / vibe / impression”

느낌 comes from the verb 느끼다 = “to feel.”

It refers to:

Internal feelings

Impressions

Vibes

A general “sense” about something

👉 It’s not usually a physical sense like taste or touch. It’s more emotional or intuitive.

Example:

이 노래 느낌 좋다.

→ “This song has a good vibe.”

(Not “good feeling” literally — more like the vibe is nice.)

🔎 But in daily life…

Korean doesn’t always say “I feel cold/sad/bored” using 느낌.

Instead, Koreans usually just use descriptive adjectives directly:

추워요 = I’m cold.

슬퍼요 = I’m sad.

심심해요 = I’m bored.

Saying:

❌ 추위를 느껴요

sounds a bit dramatic — like you’re narrating a documentary about your own life.

When you DO use 느끼다

You use 느끼다 when you’re talking about experiencing something more abstract or reflective:

추위를 느껴요 = I feel the cold.

슬픔을 느꼈어요 = I felt sadness.

This sounds:

More literary

More emotional

More thoughtful

It’s like the difference between:

“I’m sad.”

vs“I felt a deep sense of sadness.”

2️⃣ 감 (感) — the “-ness” or emotional state builder

감 is a Sino-Korean root that builds abstract emotional nouns.

Think of it like an emotional LEGO block 🧱

Examples:

자신감 = self-confidence

죄책감 = guilt

성취감 = sense of achievement

It turns ideas into emotional states.

Important:

You can sometimes replace 느낌 with 감,

but you cannot use 감 as a verb like 느끼다.

You say:

자신감을 느꼈어요.

→ I felt confidence.

NOT:

❌ 자신감을 감했어요.

감 creates the emotion-noun.

느끼다 is what you do with it.

3️⃣ 각 (覺) / 감각 (感覺) — “sense / sensory awareness”

This is more physical or perceptual.

Think biology class 👀👂👃👅✋

미각 = taste

시각 = sight

촉각 = touch

청각 = hearing

후각 = smell

감각 = sense (general sensory ability)

This is about your sensory system, not your emotional vibe.

What about the verb 감각하다?

Technically it exists in the dictionary, but almost nobody uses it in daily speech.

Instead, Koreans say:

감각이 있다 = to have good sense (at style/art/timing/cooking)

감각이 없다 = to have no sense

Example:

그 코디네이터는 패션 감각이 없어요.

→ “The coordinator has no fashion sense.”

This is closer to “aesthetic sense” or “instinct.”

🔥 Quick Comparison Table

🎯 Simple Way to Remember

느낌 = vibe

감 = emotional state

감각 = sensory system

느끼다 = to feel or experience something internally

하다 vs 되다

What are the differences between하다 and 되다?

하다 vs 되다 (with Sino-Korean nouns)

1. Core difference

하다 (active voice)

The subject intentionally performs the action.

Focus = who did it

되다 (passive / result-focused)

The subject is affected by the action or reaches a result/state.

Focus = what happened / the outcome, not the doer.

2. Meaning contrast in simple terms

하다

되다

“SUBJECT” acts

“AN EVENT” has acted

“SUBJECT” = The doer

“SUBJECT” = The event being acted

The nuance contains more will and control by the DOER

The nuance sounds more official, and neutral

3. Example pairs

① 청소하다 / 청소되다

호텔리어가 방을 청소했어요.

The hotelier cleaned the room. (“The HOTELIER” did it)

객실이 깨끗하게 청소되었어요.

The room has been cleaned. (We care about the result, not who cleaned it)

→ We can find many “되다” expressions from announcements in workplaces, hospitals, clinics, and hotels so on.

② 시작하다 / 시작되다

우리는 리허설을 3시에 시작했어요.

We started the rehearsal at 3.

리허설이 3시에 시작됐어요.

The rehearsal has started at 3.

✔ 하다 → 누가 시작했는지 중요 ; It slightly more focuses on WHO did the rehearsal.

✔ 되다 → 사건 자체가 중요 ; It slightly more focuses on the fact that the rehearsal was started.

③ 승인하다 / 승인되다

회사가 제 휴가를 승인했어요.

The company approved my leave.

제 휴가가 승인되었어요.

My leave was approved.

→ 승인되었습니다 / 접수되었습니다 / 처리되었습니다 so on are written in the official announcement, business emails, and the administration documents very frequently.

④ 결정하다 / 결정되다

우리는 공연 날짜를 결정했어요.

We decided the performance date.

; It slightly focused on the fact “WE” decided the date more.

공연 날짜가 결정되었어요.

The performance date has been decided.

; It slightly focused on the fact “The date was decided.” more.

⑤ 변경하다 / 변경되다

고객이 예약 시간을 변경했어요.

The client changed the reservation time.

; It slightly focused on the fact “THE CLIENT” changed time more.

예약 시간이 변경되었습니다.

The reservation time has been changed.

; It slightly focused on the fact “Reservation time was changed.” more.

4. Important nuance: “되다 = 더 부드럽고 객관적”

In Korean, the word "되다" is used often to blur the responsibility of the subject or make it sound official.

한국어에서는 주체 대상의 책임을 흐리게 하거나, 공식적으로 들리게 하기 위해 “되다.” 를 많이 씁니다.

Example sentences:

그 C.E.O.는 정책을 철회했습니다.

The C.E.O. has withdrawn the policy.

( It sounds direct and focuses on the action’s SUBJECT. )

정책이 철회됐습니다.

The policy has been withdrawn.

( It sounds official and neutral. )

5. Native-like contrast example

선생님이 시험을 취소했어요.

The teacher canceled the exam. (slightly focuses on the fact that the TEACHER canceled.)

시험이 취소됐어요.

The exam was canceled. (neutral, no asking who did.)

6. very common 하다/되다 pairs

하다

되다

준비하다 to prepare

준비되다 to be prepared

완료하다 to complete

완료되다 to be completed

접수하다 to register

접수되다 to be registered

발송하다 to send

발송되다 to be sent

예약하다 to reserve

예약되다 to be reserved

공지하다 to announce

공지되다 to be announced

설치하다 to install

설치되다 to be installed

개발하다 to develop

개발되다 to be developed

Example sentences: :

앱이 아직 설치되지 않았어요.

The app hasn’t been installed yet.

매니저가 앱을 아직 설치하지 않았어요.

The manager hasn’t installed the app, yet.

모든 vs 모두

What is the difference between 모든 vs 모두?

📘 The Difference Between 모두 and 모든

A common mistake among Korean learners is confusing 모두 and 모든.

Both relate to the idea of “all,” but their grammar roles are quite different.

1. 모두 [modu] = adverb / pronoun

👉 Means “all (of them)”

👉 Can stand alone as the subject or adverb

👉 Often used with particles like -가, -를

✅ Grammar role:

Adverb: modifies the verb

Pronoun: replaces the noun (“everyone / everything”)

Examples:

학생들이 모두 왔어요.

→ All the students came.

우리는 케이크를 모두 먹었어요.

→ We ate all the cake.

친구들이 모두가 그 영화를 좋아해요.

→ All of my friends like that movie.

질문에 모두가 대답했어요.

→ Everyone answered the questions.

선생님은 우리 모두를 사랑해요.

→ Our teacher loves all of us.

👉 Notice:

모두 = can replace the whole noun phrase

= everyone / everything / all of them so on

2. 모든 (modeun) = determiner

👉 Means “every” / “all”

👉 Must always come before a noun

👉 Cannot be used alone

✅ Grammar role:

Determiner → modifies a noun directly

Examples:

모든 학생이 시험을 봤어요.

→ Every student took the exam.

정현 씨는 모든 책을 다 읽었어요.

→ Junghyun read all the books.

소현 씨의 모든 동물들이 너무 사랑스러워요.

→ All of Sohyun’s animals in Sohyun’s are so lovely.

이 가게는 모든 음식을 직접 만들어요.

→ This restaurant makes all the food themselves.

Mel 씨는 모든 노래를 작곡했어요.

→ Mel wrote all the songs.

👉 Notice:

모든 + noun = one noun phrase

You cannot say just 모든 by itself.

3. Side-by-side comparison

Korean

Correct?

Why

Meaning

모두 왔어요

✅

모두 can stand alone

Everyone came

모든 왔어요

❌

모든 needs a noun

(incorrect)

모든 학생이 왔어요

✅

modifies 학생

All students came

학생이 모두 왔어요

✅

모두 modifies the verb

All students came

4. Natural English analogy

This may help learners understand intuitively:

모두 ≈ all / everyone / everything

→ like a pronoun or adverb모든 + noun ≈ every + noun / all + noun

Examples:

모두 갔어요 = Everyone left

모든 사람이 갔어요 = Every person left

5. Common wrong examples

❌ 모든 먹었어요

→ incorrect because 모든 needs a noun

✅ 모두 먹었어요

→ Depending on the context, it can be

“I ate everything. / I ate it all.” or “Everyone ate. ”

❌ 모두 사람

→ incorrect

✅ 모든 사람

→ all people / everyone

✨ One-line summary

모두 = “all” by itself

모든 = “every/all” + noun

Korean Word Nominalization

Let’s learn Korean word nominalization

# Korean Nominalization: –기, –(으/느)ㄴ 것, –(으)ㅁ

In Korean, you can turn a verb or adjective into a noun (or noun clause) in three main ways:

* –기

* –(으/느)ㄴ 것

* –(으)ㅁ

There is no perfectly strict grammar rule that separates them.

The best way to master them is through exposure to many examples.

However, each form does have a **general tendency and feeling**.

1. –기

: Unfinished action, general activity, emotions, habits, potential

**–기** focuses on the **action itself**, often something not yet completed or something discussed generally.

It is commonly used with:

* Emotion-related adjectives: 좋다, 싫다, 어렵다, 힘들다, 무섭다, etc.

* Verbs like: 바라다, 희망하다, 시작하다, 좋아하다, 싫어하다

###Examples

• 이 의자는 오래 앉기에 편해요.

→ This chair is comfortable to sit on for a long time.

• 혼자 여행하기 무서워요.

→ I’m scared of traveling alone.

• 한국어 발음 배우기가 생각보다 어려워요.

→ Learning Korean pronunciation is harder than expected.

• 숙제를 다 하기가 힘들어요.

→ It’s hard to finish homeworks.

• 아이들은 놀기를 정말 좋아해요.

→ Children really like playing.

• 부모님을 실망시키기 싫어요.

→ I don’t want to disappoint my parents.

• 올해 안에 취업하기를 바랍니다.

→ I hope to get a job within this year.

### Summary feeling

–기 = “the act of doing something” (unfinished, general, emotional target)

It is also used in idioms:

* 식은 죽 먹기 → Piece of cake

* 하늘의 별 따기 → Almost impossible

2. –(으)ㅁ

: Finished action, realized fact, judgment, report

**–(으)ㅁ** sounds more **factual and formal**.

It is often used when the speaker treats the information as an **established fact**, such as:

* Realization

* Judgment

* Reports

* Announcements

* News

* Official documents

You can attach past tense before –음:

갔음을, 끝났음을, 알았음을

### Examples

• 그가 이미 출발했음을 알았다.

→ I knew that he had already left.

• 이 문제가 생각보다 심각함을 깨달았다.

→ I realized that this problem is more serious than I thought.

• 그 배우가 결혼했음이 공식 발표되었다.

→ It was officially announced that the actor got married.

• 그 선수가 규칙을 어겼음이 밝혀졌다.

→ It was revealed that the player broke the rules.

• 그 제품이 위험함이 증명되었다.

→ It was proven that the product is dangerous.

### Common in written/formal style

You often see –음 in:

* News headlines

* Reports

* Official documents

Examples:

* 도로가 통제되었음.

→ The road has been closed.

* 시험 일정 변경됨.

→ Exam schedule changed.

### Summary feeling

–(으)ㅁ = “confirmed fact / formal statement”

3. –(으/느)ㄴ 것

: Most neutral and flexible form

**–(으/느)ㄴ 것** is the most commonly used form in daily conversation.

It is neutral and flexible, and in many cases can replace both –기 and –(으)ㅁ.

### Examples

• 요리하는 것이 재미있어요.

→ Cooking is fun.

• 새로운 사람을 만나는 것이 좋아요.

→ I like meeting new people.

• 그가 약속을 어긴 것을 알고 있었다.

→ I knew that he broke the promise.

• 네가 노력하고 있는 것을 알아.

→ I know that you are trying.

• 무서운 것은 싫어요.

→ I hate scary things.

### Comparison

• 집에 혼자 있는 것이 싫어요.

= 집에 혼자 있기 싫어요.

→ I don’t like being home alone.

• 그가 거짓말하고 있는 것이 분명해요.

= 그가 거짓말하고 있음이 분명해요.

→ It’s clear that he is lying.

• 지구의 온도가 4도 상승한 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.

= 지구의 온도가 4도 상승했음이 밝혀졌습니다.

→ It turned out that the Earth's temperature rose by 4 degrees Celsius.

### Summary feeling

–는 것 = safest, most natural choice in conversation

If learners are unsure which form to use, **using –는 것 is usually the best option**.

## Simple Comparison Chart

Form

Core feeling

–기

Action itself, unfinished, emotional

–(으)ㅁ

Confirmed fact, judgment, formal

–는 것

Neutral, conversational, Daily speech, flexible replacement

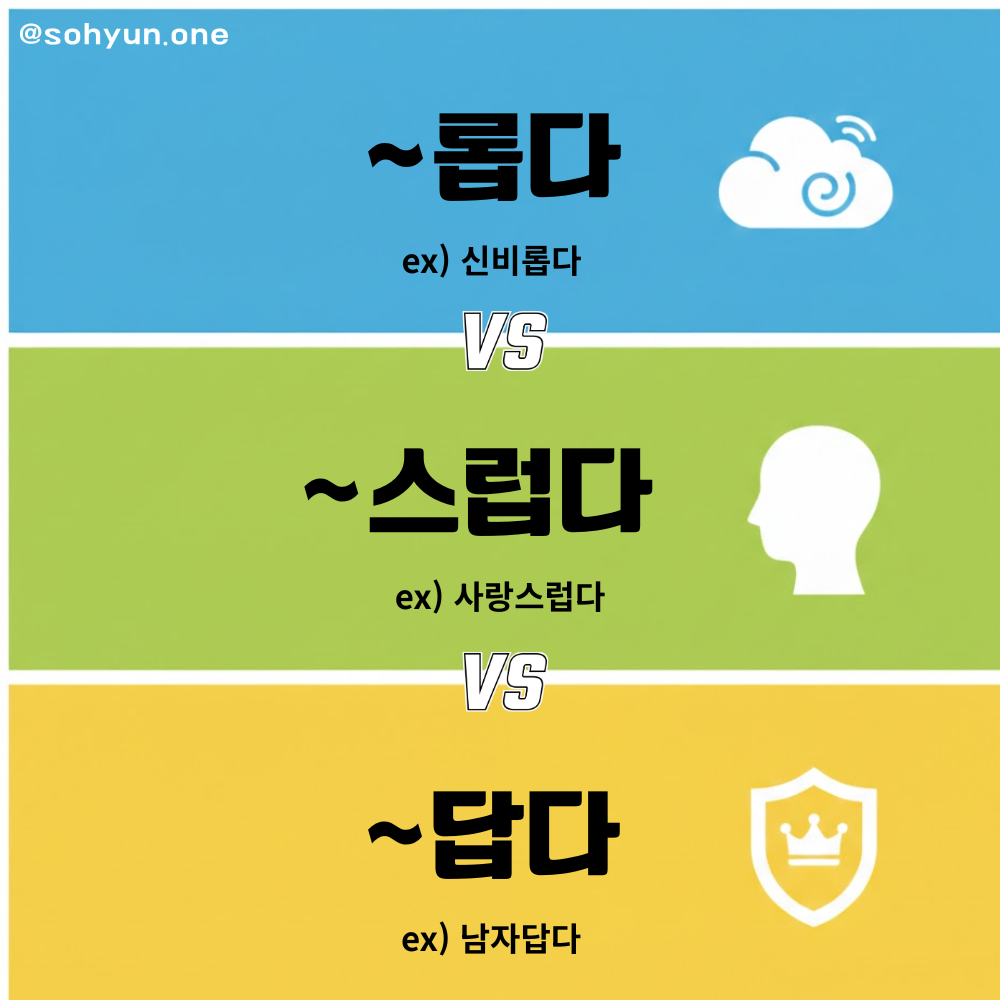

롭다 vs 스럽다 vs 답다

What are the differences between ~롭다, ~스럽다 and ~답다?

I would like to inform you that there is a difference like this overall, although it does not apply 100% to all expressions, so please make you exposured to real Korean conversations a lot such as TV show, movies or your favorite Genre’s Korean Youtube channel so on.

1. –롭다 (-ropda)

Meaning:

The quality is strong, inherent, or naturally abundant in the subject.

It describes a trait that feels deeply embedded, not just on the surface.

Examples

신비롭다 → mysterious (mystery feels deeply present)

외롭다 → lonely (loneliness is strongly felt)

자유롭다 → free

평화롭다 → peaceful

Sentence

우주는 항상 신비로워요.

The Universe is mysterious always. (The universe genuinely gives off a strong mysterious aura.)

2. –스럽다 (-seureopda)

Meaning:

It seems like the subject has that quality, or it gives that impression or feeling.

More subjective and based on perception.

Examples

신비스럽다 → seems mysterious

사랑스럽다 → lovable (gives a lovely feeling)

자연스럽다 → natural (feels natural)

부담스럽다 → feels burdensome

Sentence

뉴진스의 최신 앨범 노래는 신비스러워요.

The song of New Jeans’ latest album sounds mysterious. (It’s more about the impression he gives.)

3. –답다 (-dapda)

Meaning:

The subject is befitting of a role, identity, or standard.

It evaluates whether someone/something matches what is expected.

Examples

남자답다 → manly (fits what is expected of a man)

어른답다 → adult-like (behavior-wise, thoughts-wise)

학생답다 → like a proper student

정치인답다 → like a politician

Sentence

요즘 정치인다운 정치인들이 별로 없어요.

There are not many politicians who are like politicians these days..

Natural contrast with your example

Korean

Natural English nuance

우주는 신비로워요.

The universe is mysterious (strong, inherent aura).

노래가 신비스러워요.

The song sounds mysterious (based on impression).

정치인다운 정치인이 없어요.

There is no politicians who are like politicians.

Simple one-line summary (great for learners)

–롭다 = the quality is really there

–스럽다 = the quality is felt / seems to be there

–답다 = the quality matches what it should be

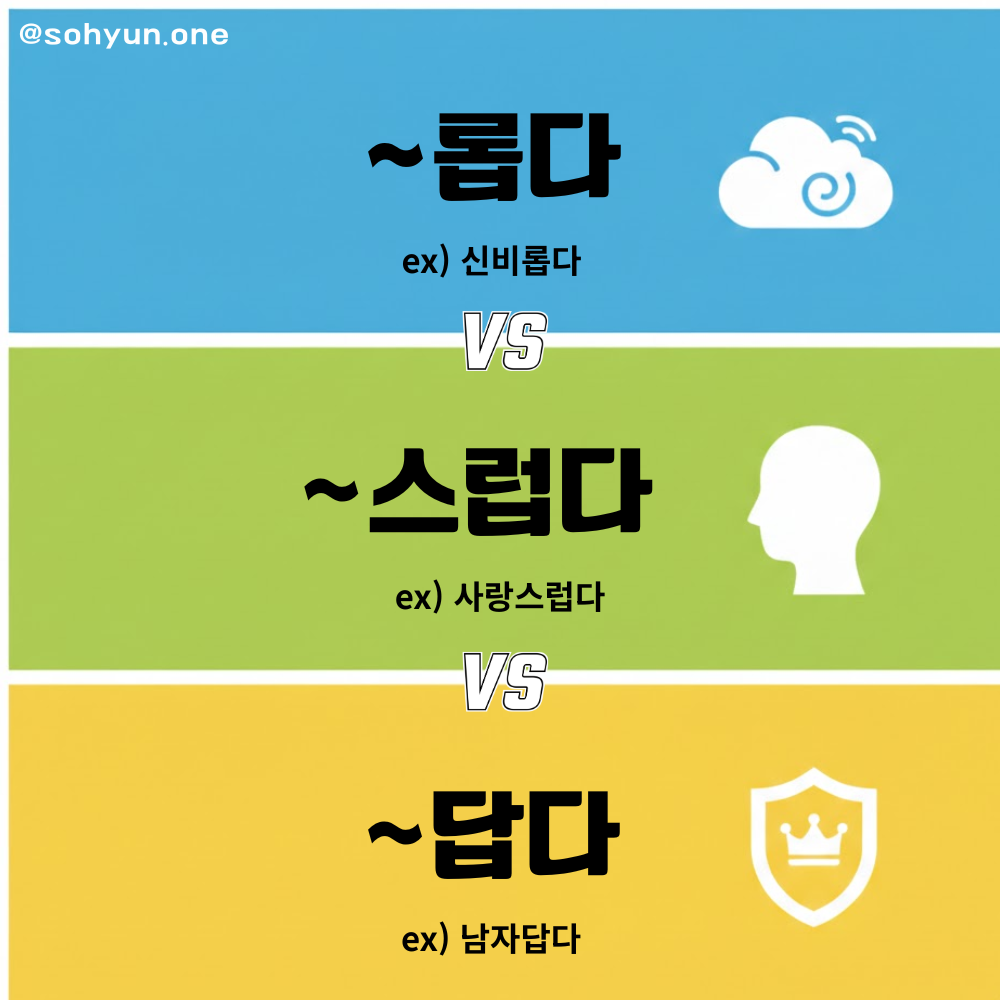

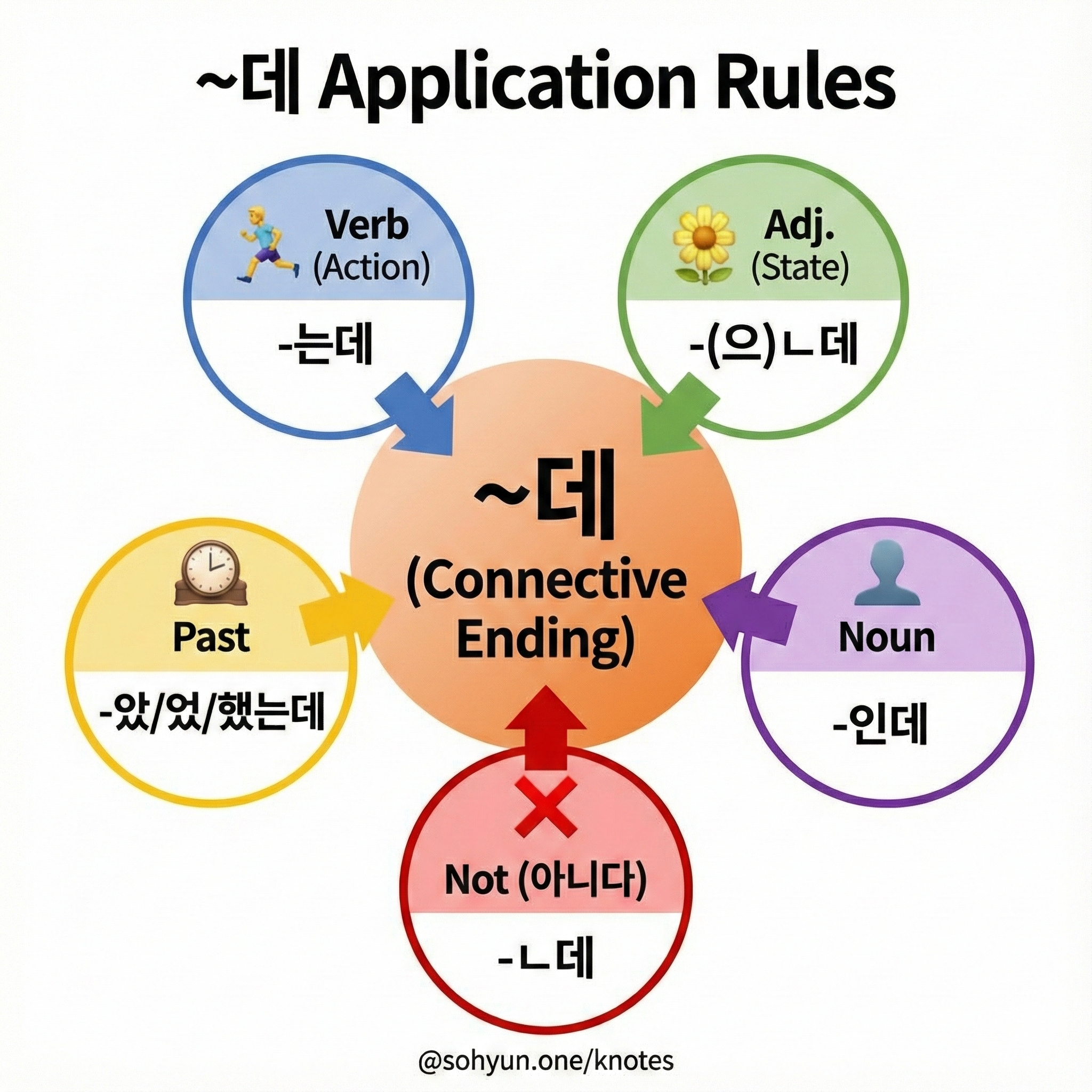

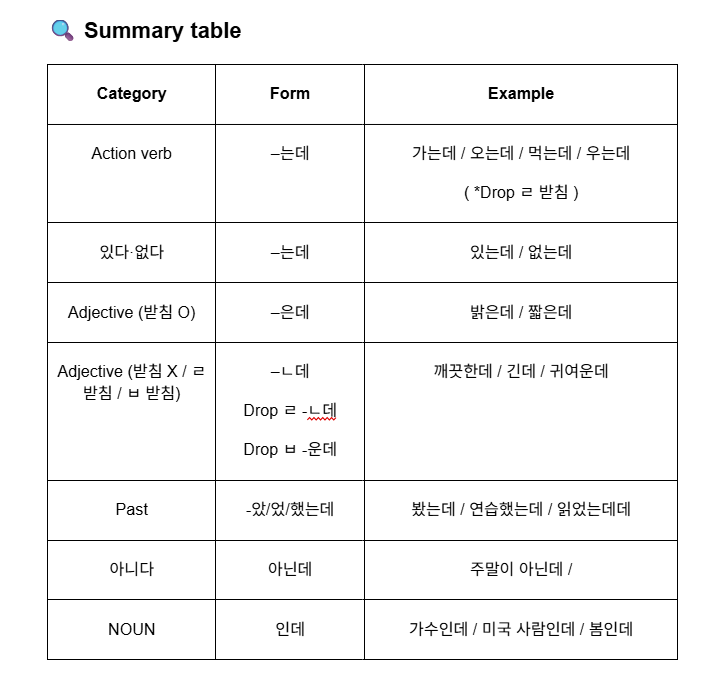

How to apply ~데 depending on verb / adjective / NOUN so on

How to apply ~데 depending on verb / adjective / NOUN so on

1️⃣ –는데 (verb / 있다·없다)

When to use

Action verbs (하다, 가다, 먹다, 오다 등)

있다 / 없다

Progressive or general actions

Grammar logic

Verbs take –는 in present descriptive clauses → –는데

Examples

지금 비가 오는데 우산 있어요?

→ It’s raining right now, so / given that, do you have an umbrella?저는 회사에 가는데 시간이 좀 걸려요.

→ I go to work, and it takes some time.지금 현금이 없는데 어떻게 해야 할까요?

→ I don’t have cash now, so what should I do?아이가 자고 있는데 너무 조용해요.

→ The child is sleeping, so it’s very quiet.

English explanation

Used when the preceding clause describes an action or ongoing state,

providing background or contrast.

l Exception) When the verb stem ending is ㄹ, drop ㄹ and add 는데.

❌ 돈은 많이 벌은데 시간이 없어요.

돈은 많이 버는데 시간이 없어요. (I make a lot of money, but time.)

2️⃣ –은데 / –ㄴ데 (adjectives)

When to use

Descriptive adjectives (춥다, 비싸다, 예쁘다, 어렵다 등)

Choice depends on 받침 (final consonant)

Form rule

받침 있으면 (If there is Batchim) → –은데

ㄹ 받침 있으면 (If there is ㄹ Batchim) → Drop ㄹ and –ㄴ데

ㅂ 받침 있으면 (If there is ㅂ Batchim) → Drop ㅂ and 운데

받침 없으면 (If there is no Batchim) → –ㄴ데

Examples

오늘 날씨가 추운데 바람도 불어요.

→ It’s cold today, and it’s also windy.이 가방이 비싼데 너무 예뻐요.

→ This bag is expensive, but it’s very pretty.가을이는 귀여운데 똑똑해요.

→ Ga-eul is cute, and (even) smart.이 문제는 어려운데 설명해 줄게요.

→ This quiz is difficult, so I’ll explain it.리사는 다리가 긴데 얼굴은 작아요.

→ Lisa has long legs, but her face is small.

English explanation

Adjectives describe states or qualities,

so they take –은/–ㄴ before –데, not –는.

3️⃣ Past reference: –았/었/했는데

When to use

Talking about a past situation as background

Applies to both verbs and adjectives

Examples

어제는 비가 왔는데 오늘은 맑아요.

→ It rained yesterday, but today it’s sunny.그 영화 재미있었는데 끝이 좀 아쉬웠어요.

→ The movie was fun, but the ending was a bit disappointing.예전에 여기 살았는데 다른 동네에 살아요.

→ I used to live here, but I live in a different neighborhood.

English explanation

The past marker –았/었/했– comes before –는데,

because –데 connects clauses, not tense.

4️⃣ Special note: 아니다 → –ㄴ데

아니다 ( am not / is not / are not ) is applied like an adjective with -ㄴ데

Example

그건 제 잘못이 아닌데요.

→ That’s not my fault, though.그 여자들은 한국 사람이 아닌데 한국말을 잘 해요.

→ Those women are not Koreans, but they speak Korean so well.

5️⃣ 명사 + 인데

When to use

The preceding clause ends in a noun

You want to give background, contrast, explanation, or conversation starter so on.

Very common in spoken Korean

Grammar logic

Nouns cannot take –는 or –은/–ㄴ directly.

So Korean uses “Noun + (이)다 + –ㄴ데 -> NOUN인데”

Examples (background / explanation)

오늘 평일인데 회사에 사람이 없어요.

→ It’s a weekday today, and there aren’t many people at the office.지금 점심시간인데 식당 앞에 줄이 길어요.

→ It’s lunchtime, and there is a long waiting line in front of the restaurant.저 사람은 댄서인데 왜 그렇게 춤을 못 춰요?

→ That person is a dancer, but why is he that bad at dancing?

Examples (contrast)

그 사람은 학생인데 회사를 운영해요.

→ He’s a student, and he runs a company.겨울인데 눈이 많이 안 내려요.

→ It’s winter, but it doesn’t snow that much.

Examples (soft lead-in / conversation starter)

Very common in natural speech:

이게 Wi-fi QR 코드인데 스캔해 보세요.

→ This is the Wi-fi QR code, so please scan it.제가 좋아하는 노래인데 같이 들을래요?

→ This is a song I like, so would you like to listen to it together?

🚫 Common learner mistakes

❌ 오늘 덥은데 패딩을 입었어요.

✔ 오늘 더운데 옷을 많이 입었어요

→ It’s hot today, but I wore a padded jacket.

❌ 고양이가 울는데 아이가 우는 것 같아요.

✔ 고양이가 우는데 아이가 우는 것 같아요.

→ A cat is crying, and it sounds like a baby is crying.

❌ 줄이 길은데 그냥 기다리고 있어요

✔ 줄이 긴데 그냥 기다리고 있어요

→ The waiting line is long, but we just are waiting in a line.

❌ 이 옷은 너무 귀엽은데 비싸요.

✔ 이 옷은 너무 귀여운데 비싸요.

→ This cloth is so cute, but it’s expensive.

🎯 One-line memory rule

Action → –는데

Adjective Description → –은/–ㄴ데

Past → –았/었/했는데

아니다 → 아닌데

NOUN → 인데

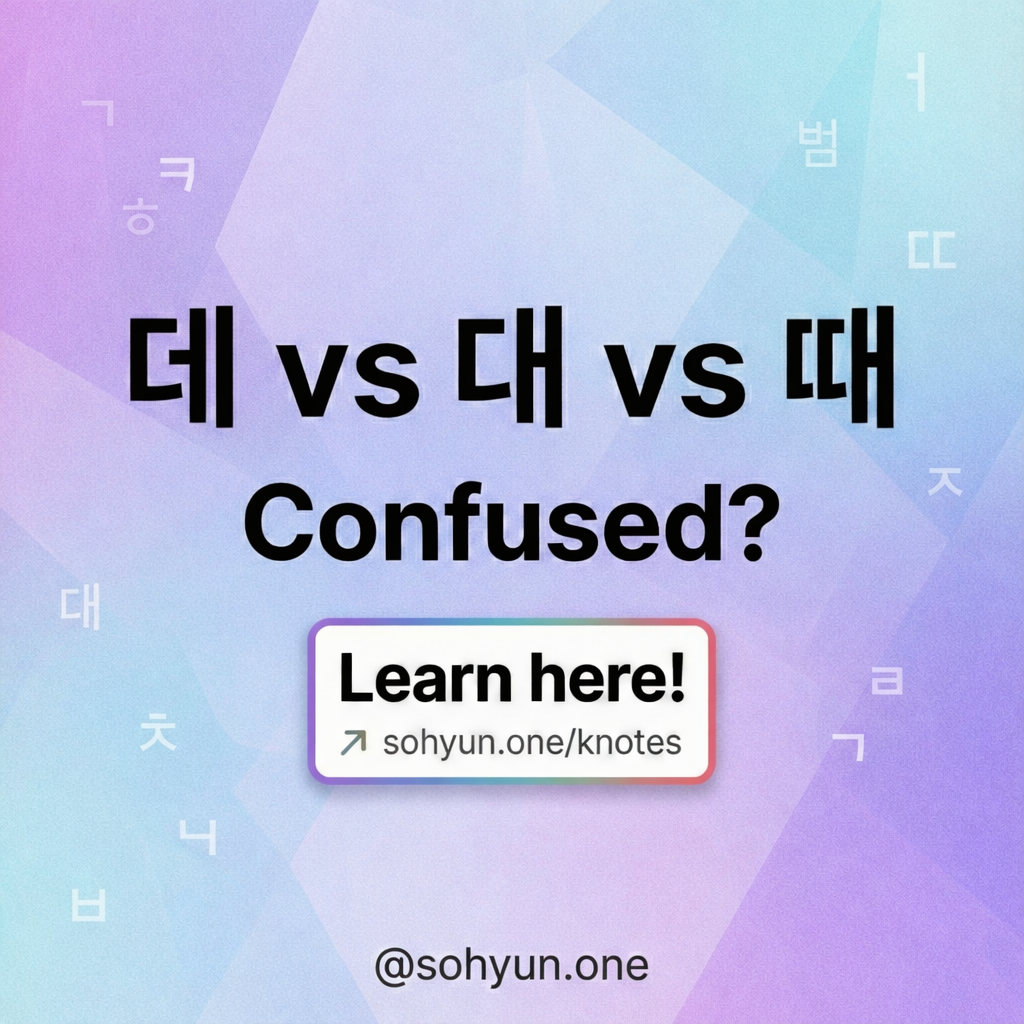

The differences of 데, 대 and 때

The differences of 데, 대 and 때

1️⃣ –데

Function: background, contrast, soft connection

–데(요) is not a standalone tense or quote.

It provides background information, sets a context, or shows contrast, often implying “so / but / and then”.

Grammatically, –데 almost always appears as –는데 / –은데 / –ㄴ데 depending on the verb/adjective.

Key idea

“Here’s some context… (and based on that…)”

Examples

오늘 추운데 인사동에서 야외 공연을 했어요.

→ It’s cold (background), but we did the outdoor performance in Insa-dong.이 카페는 예쁜데 커피가 비싸요.

→ The cafe is pretty but the coffee is expensive.비가 오는데 우산 있어요?

→ It’s raining (given that), do you have an umbrella?지금 마트에 가는데, 뭐 좀 사다 드릴까요?.

→ I’m going to go to a mart now, so would you like me to get you something?

Learner tip

❌ –데 does NOT mean “when”

❌ –데 does NOT quote anyone

✔ Think of it as context + implication

2️⃣ –대(요)

Function: hearsay / quoting what someone said

–대(요) comes from –다고 해요.

It is used when you’re reporting information you heard from someone else.

Key idea

“This is what I heard someone say.”

Examples

친구가 오늘 춥대요.

→ My friend says it’s cold, today.크리스마스에 눈이 온대요.

→ I heard it will snows in Christmas.그 식당 맛있대요.

→ People say that restaurant is good.의사 선생님이 쉬어야 한대요.

→ The doctor said I need to rest.

Learner tip

✔ Always involves someone else’s words or information

✔ Often used in casual spoken Korean

❌ Not used for your own direct feelings

3️⃣ –때

Function: time (“when”)

–때 is a noun meaning “time”.

It attaches to verbs/adjectives to mean “when / at the time that”.

Key idea

“At the time when…”

Examples

추울 때 패딩을 입어요.

→ When it’s cold, I wear a padded jacket.한국에 처음 왔을 때 많이 힘들었어요.

→ When I first came to Korea, it was very hard.아플 때 병원에 가세요.

→ Go to see a doctor when you’re not feeling well.어릴 때 이 동네에 살았어요.

→ I lived in this neighborhood when I was young.

Learner tip

✔ Can be replaced by “when” in English

✔ Often followed by 에 ( ~ 때에)

❌ No implication, no hearsay -> just time

🚫 Common learner mistakes

❌ 오늘 추울 대 목도리를 안 가져왔어요

✔ 오늘 추운데 목도리를 안 가져왔어요

❌ 친구가 아플 데 같이 병원에 갔어요

✔ 친구가 아플 때 같이 병원에 갔어요

🎯 One-sentence memory trick

데 → “Here’s the situation…”

대 → “I heard that…”, “Someone said…”

때 → “When…”

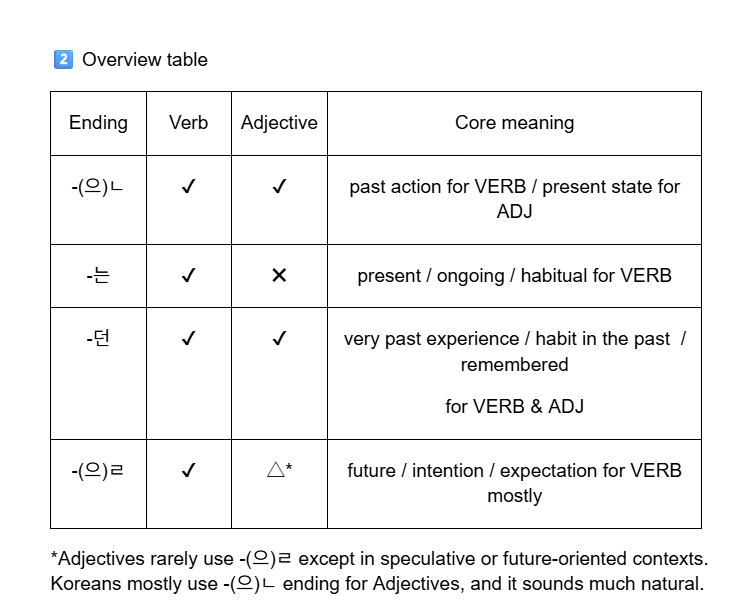

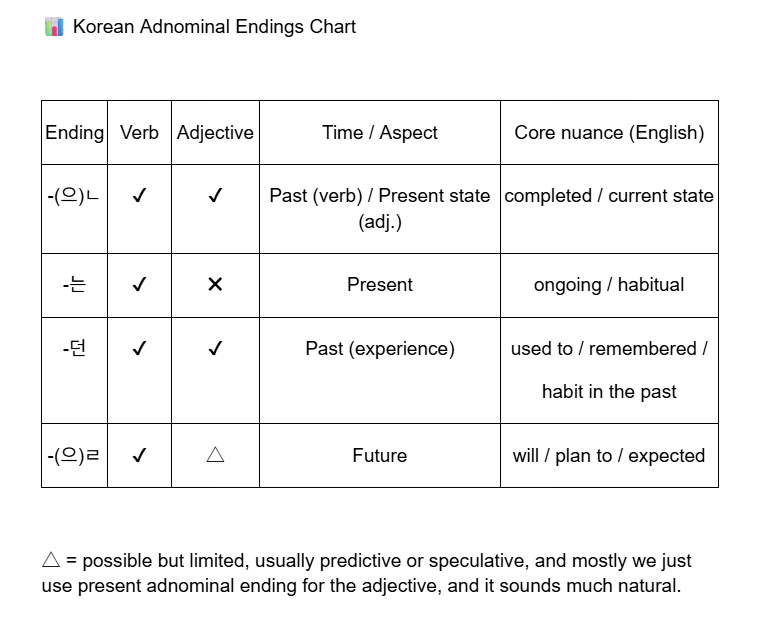

Adnominal endings in Korean

How to modify NOUN with ADJECTIVE & VERB using Adnominal endings in Korean?

Korean Adnominal Endings (관형사형 어미)

-(으)ㄴ, -는, -던, -(으)ㄹ

(How verbs & adjectives modify nouns by tense)

1️⃣ What are adnominal endings?

In Korean, verbs and adjectives can directly modify nouns by changing their endings.

These endings show tense, aspect, and speaker perspective, similar to English relative clauses.

📌 English:

The book that I read

📌 Korean:

읽은 책

(No “that / which / who” — tense is shown by the ending “은” here.)

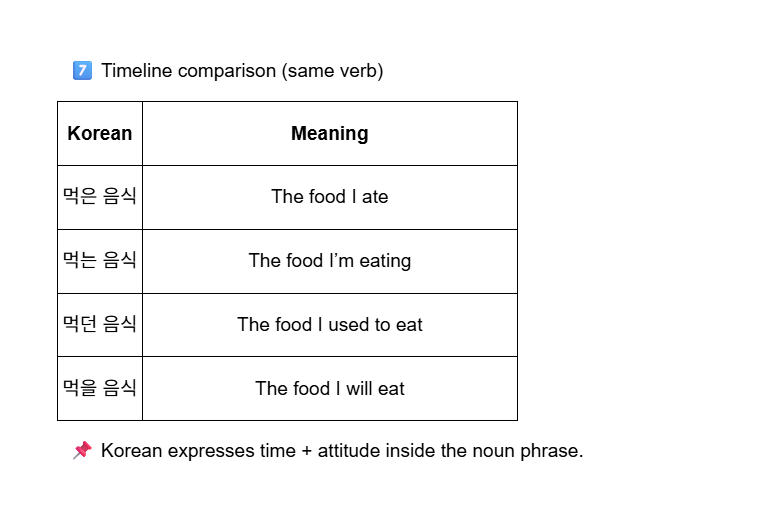

Adjectives rarely use -(으)ㄹ except in speculative or future-oriented contexts. Koreans mostly use -(으)ㄴ ending for Adjectives, and it sounds much natural.

3️⃣ -(으)ㄴ : past (verbs) / present state (adjectives)

🔹 With verbs: completed past action

Use -(으)ㄴ when the action is finished.

그 남자가 입은 바지

→ The pants the guy wore

하와이에서 산 가방

→ The bag I bought in Hawaii

처음 만난 사람

→ The person I met for the first time

📌 This corresponds to English past tense relative clauses.

🔹 With adjectives: current, fixed state

Adjectives describe a state, so -(으)ㄴ shows the present condition.

예쁜 꽃

→ A pretty flower

밝은 색

→ A bright color

조용한 거리

→ A quiet street

📌 Even though the ending looks “past,” it does NOT mean past for adjectives.

4️⃣ -는: present / ongoing / habitual (verbs only)

🔹 With verbs ONLY

Use -는 for actions that are:

happening now

habitual

generally true

지금 읽는 책

→ The book I’m reading now

매일 가는 카페

→ The cafe I go to every day

요즘 배우는 운동

→ The sport I’m learning these days

★ Adjectives do NOT use -는

❌ 예쁘는 사람

⭕ 예쁜 사람

5️⃣ -던 : past experience, memory, or incomplete action

🔹 Key idea (important!)

-던 refers to:

something experienced in the past

often not completed

often recalled from memory

It frequently adds nostalgia, contrast, or background feeling.

🔹 With verbs: past, ongoing, or habitual in the past

어릴 때 자주 가던 공원

→ The park I used to go to often when I was little

내가 살던 집

→ The house I used to live in

늘 먹던 음식

→ The food I used to eat

📌 English equivalents:

used to

would

that I remember

habitually

🔹 With adjectives: remembered past state

20년 전에 인기가 많던 아이돌 그룹

→ The idol group that had been popular 20 years ago

어렸을 때 유행하던 물건

→ The item that had been trendy when I was little

항상 조용하던 학생

→ The student that had been quiet always

📌 Often implies:

“It was like that then (but maybe not now).”

6️⃣ -(으)ㄹ: future/intention/expectation (verbs mostly)

🔹 With verbs: future or planned action

Use -(으)ㄹ for actions that have not happened yet.

다음 주에 볼 시험

→ The exam I will take next week

곧 만날 사람

→ The person I will meet soon

내년에 할 프로젝트

→ The project I will do next year

📌 This includes:

future

intention

expectation

assumption

🔹 With adjectives (limited, speculative)

Adjectives can use -(으)ㄹ when the meaning is uncertain or expected.

5년 뒤에 더 비쌀 집

→ The house that will probably be more expensive 5years later

미래에 살기 가장 좋을 나라

→ The country that will be best to live in the future

📌 This sounds predictive, not descriptive, and in a real conversation we use present adnominal ending for the adjective mostly, and it sounds much natural.

8️⃣ Key learning tips for English speakers

Korean modifiers come before the noun

No relative pronouns

One ending = tense + nuance

-던 is about memory, habit, a state before it changed and experiences in the past, not just time

9️⃣ One-sentence summary

Korean adnominal endings compress tense, aspect, and speaker perspective into one verb ending before the noun.

8️⃣ Key learning tips for English speakers

Korean modifiers come before the noun

No relative pronouns

One ending = tense + nuance

-던 is about memory, habit, a state before it changed and experiences in the past, not just time

9️⃣ One-sentence summary

Korean adnominal endings compress tense, aspect, and speaker perspective into one verb ending before the noun.

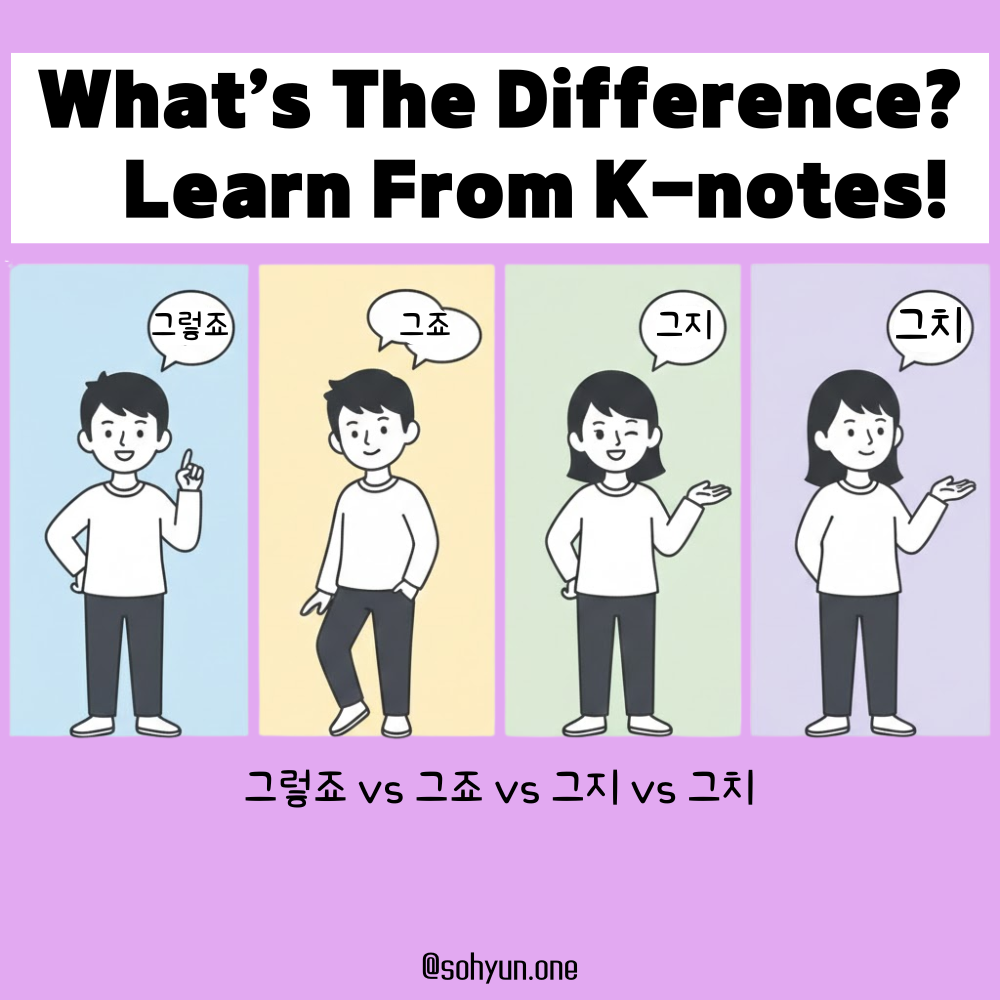

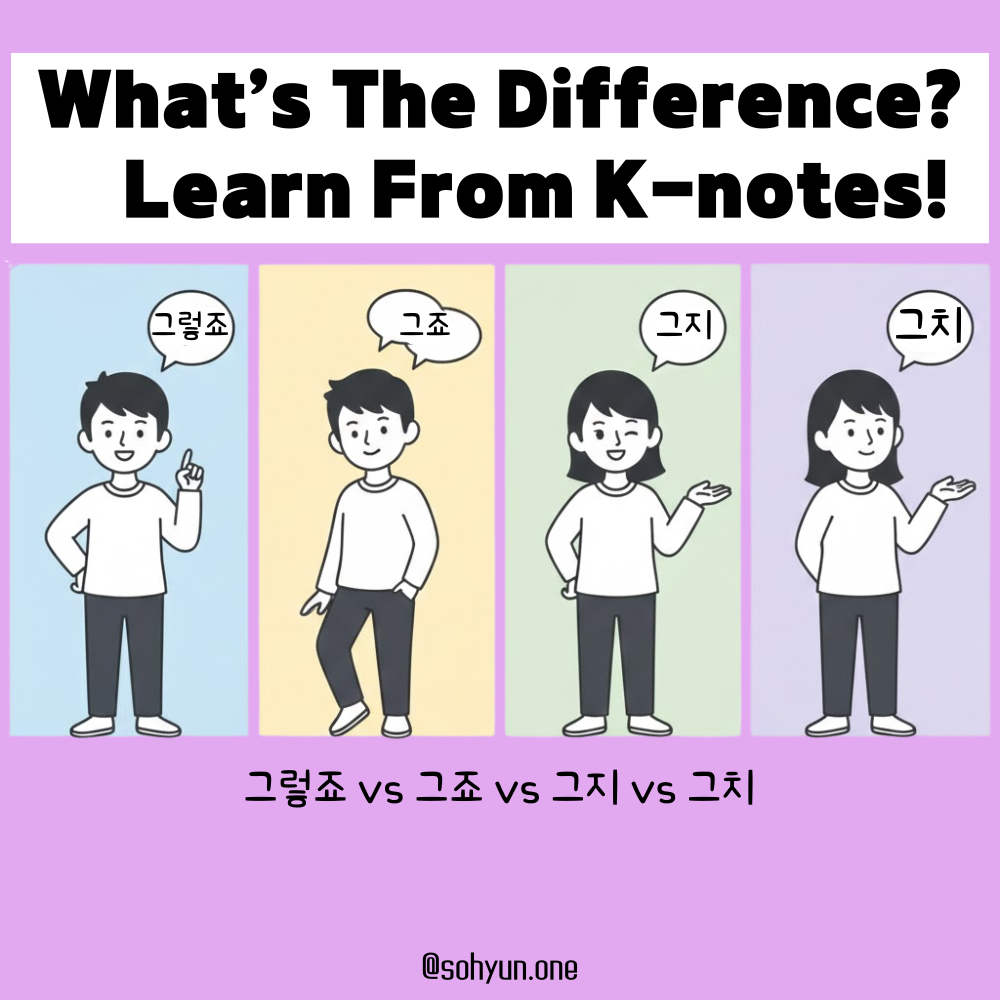

그렇죠 vs 그죠 vs 그지 vs 그치

Ø How are they different “그렇죠, 그죠, 그지 and 그치”?

🌟 Korean Confirmation Expressions: 그렇죠 / 그쵸 / 그지 / 그치

You’ll hear these expressions constantly in daily Korean.

They all relate to seeking or showing agreement, but they differ in formality, spelling, and nuance.

1) 그렇죠 / 그쵸

Meaning:

“Right?”, “Isn’t it?”, “I know, right?”, “Exactly.”

Notes:

그쵸 is just the shortened spoken form of 그렇죠.

Both mean the same, but 그렇죠 is more standard and can be used in polite, official and formal conversation.

Built from 그렇다 + 지요 → 그렇지요 → 그렇죠 (sound contraction)

, and this ending “지요/죠” can be added to an adjective/verb stem.

According to Korean grammar, 그쵸 is not counted as standard word, but still many Koreans say the word in general life because of the convenience of the pronunciation.

✔ Asking for confirmation

오늘 정말 춥죠?

It’s really cold today, right?이 영화 재미있죠?

This movie is good, right?정현 씨는 노래를 정말 잘 부르죠?

Junghyun sings so greatly, doesn’t he?

✔ Agreeing with someone

그렇죠, 저도 고객님의 마음을 충분히 이해합니다.

Yes, you are right, I totally understand what you felt. (to a customer).그렇죠, 저도 감독님께서 말씀하신 것처럼 생각해요.

Exactly, I think same with the director said.

✔ Soft, polite conversation filler

그렇죠… 음… 그럴 수도 있죠.

Right… hmm… that could be true.

Polite, friendly, and safe for any situation.

2) 그치?

Meaning:

Casual Banmal and very spoken form of 그렇죠, and it means “right?”, “yeah?”, “don’t you think so?”

Notes:

Standard spelling is 그치?

You may hear “그지?” among very casual speakers, but the recommended spelling is 그치 to avoid confusion with 거지(= beggar), Pronunciation-wise, 그지 sounds similar to 거지.

✔ Asking for confirmation (friends)

이거 완전 귀엽지? 그치?

This is really cute, right?내가 말한 게 맞지? 그치?

What I said is correct, right?오늘 너무 춥다, 그치?

It’s really cold today, right?

✔ Agreeing casually

그치! 나도 가을이가 너무 똑똑하다고 생각했어.

Right! I thought Ga-eul is so clever too.그치, 그게 제일 좋지.

Yeah, that’s the best option.

3) 그지? (spoken)

⚠️ Be careful with spelling.

Many Koreans pronounce “그치?” as “그지?” because of relaxed articulation.

BUT when writing, 그지 strongly resembles 거지(=beggar), so it looks wrong or funny.

Example of misunderstanding:

그지? → might be read as “A beggar?” (거지?)

So ALWAYS write it as “그치?”

📌 Quick Comparison Table

Form

Register

Meaning

Notes

그렇죠 / 그쵸

Polite

“Right?”, “Exactly.”

Safe everywhere; 그쵸 = spoken form

그치?

Casual

“Right?”

Use with friends; recommended spelling

그지?

Casual

Spoken only

“Right?”

Don’t write it; sounds like “beggar”

🔍 More Natural Conversation Examples

✔ Using both asking & agreeing

A: 이 집 통닭 진짜 맛있지?

B: 그렇죠, 그래서 사람도 많잖아요.

A: The grilled chicken here is really good, right?

B: Exactly, that’s why it’s crowded.

A: 소현 씨 연기 완전 잘하죠?

B: 그치! 완전 실력 있어!

A: Sohyun is extremely good at acting, right?

B: Exactly, she is super talented!

(Polite → casual mixing depending on the speaker and listener’s relationship)

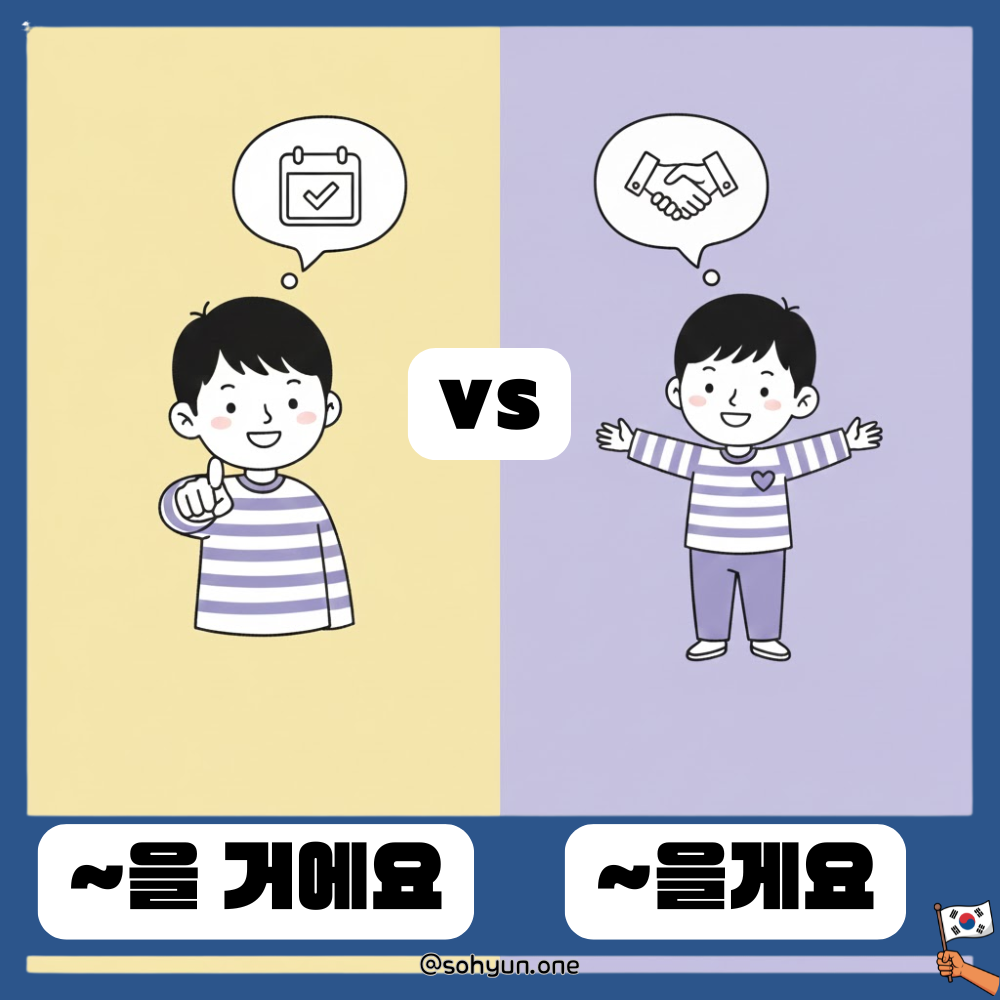

~을 거에요 vs ~을게요 vs ~겠

Ø How are they different “~ㄹ/을 거예요, ~ㄹ/을게요 and -겠-”?

🌟 Korean Future Expressions: Detailed Comparison with Examples

1) -ㄹ/을 거예요

Meaning: Prediction, intention, assumption based on evidence or your own thought.

Key point: Listener is not directly involved nor mentioned in the sentence. Near future.

💬 Examples

저는 내일 집에서 쉴 거예요.

— I will rest at home tomorrow. (just stating intention)곧 버스가 올 거예요.

— The bus will come soon. (prediction)그렇게 많이 먹으면 배 아플 거예요.

— If you eat that much, you’ll get a stomachache. (prediction based on logic)오늘은 사람이 많을 거예요.

— There will probably be a lot of people today. (assumption)아마 8시쯤 도착할 거예요.

— I will probably arrive around 8. (soft prediction)

2) -ㄹ/을게요

Meaning: Promise, voluntary action, decision made in response to the listener; interactional future.

Key point: The listener’s presence/reaction matters.

NOT used for natural phenomena or unrelated events.

💬 Examples

그럼 제가 쓰레기를 밖에 버릴게요.

— I'm going to take out the trash. (reacting to the situation)늦으면 전화할게요.

— I’ll call you if I'm late. (promise to listener)이 캐리어 제가 들게요.

— I’ll carry this suitcase (for you). (considering listener)제가 유리창을 닦을게요. 가만히 쉬세요.

— I’ll mop and clean the window. Take a rest. (decision benefiting listener)그럼 먼저 갈게요!

— Okay, I’ll go first! (closing conversation or an appointment politely)

❌ Incorrect uses:

오늘 눈 올게요.

— ❌ You cannot “promise” weather.내일 시험이 있을게요.

— ❌ The exam is not something can show voluntary action itself.

3) -겠-

Meanings:

Formal intention/promise

Strong assumption/guess

Polite softening (“I suppose…”)

Emotion or reaction (맛있겠다!)

💬 Examples

✔ Intention / promise (formal)

내일까지 보고 드리겠습니다.

— I will report back by tomorrow. (formal promise)지금 바로 확인하겠습니다.

— I will check right now.

✔ Strong guess / assumption

밖에 정말 춥겠어요.

— It must be really cold outside. (speaker’s inference)오늘 길이 많이 막히겠네요.

— I guess the traffic will be heavy today.

✔ Emotional reaction

와, 이거 정말 맛있겠다!

— Wow, this looks so delicious!피곤하겠어요.

— You must be tired. (sympathetic reaction)

📌 Spacing Rules

-ㄹ 거예요 → space needed before 거예요요

갈 거예요 / 할 거예요

-ㄹ게요 → NO space

-겠어요 / -겠습니다 → 붙여쓰기

🔍 Quick Comparison Table

Expression

Meaning / Use

Listener-involved?

Examples

-ㄹ/을 거예요

neutral future, prediction, intention

❌ No

내일 비 올 거예요.

-ㄹ/을게요

promise, decision considering listener

✔ Yes

제가 도와 줄게요.

-겠-

strong assumption, emotion, formal intention

△ Depends

맛있겠다!, 도와드리겠습니다.

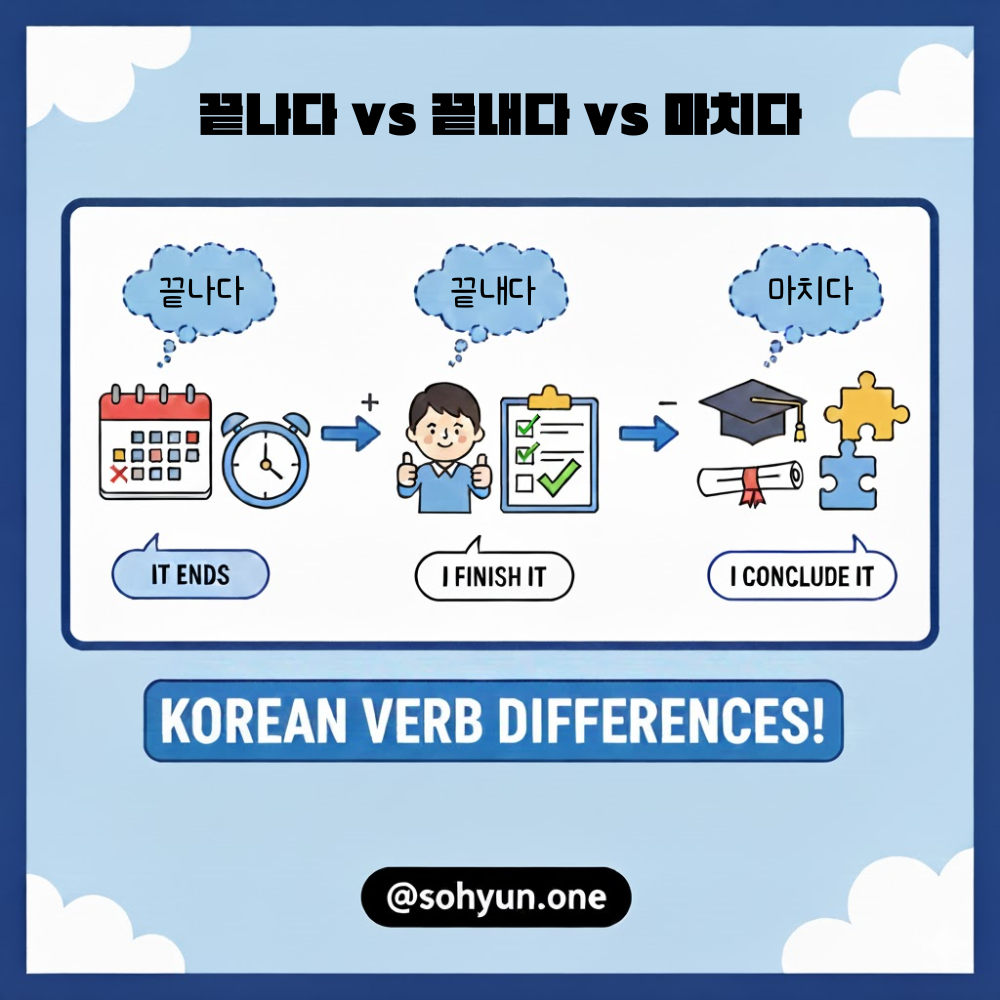

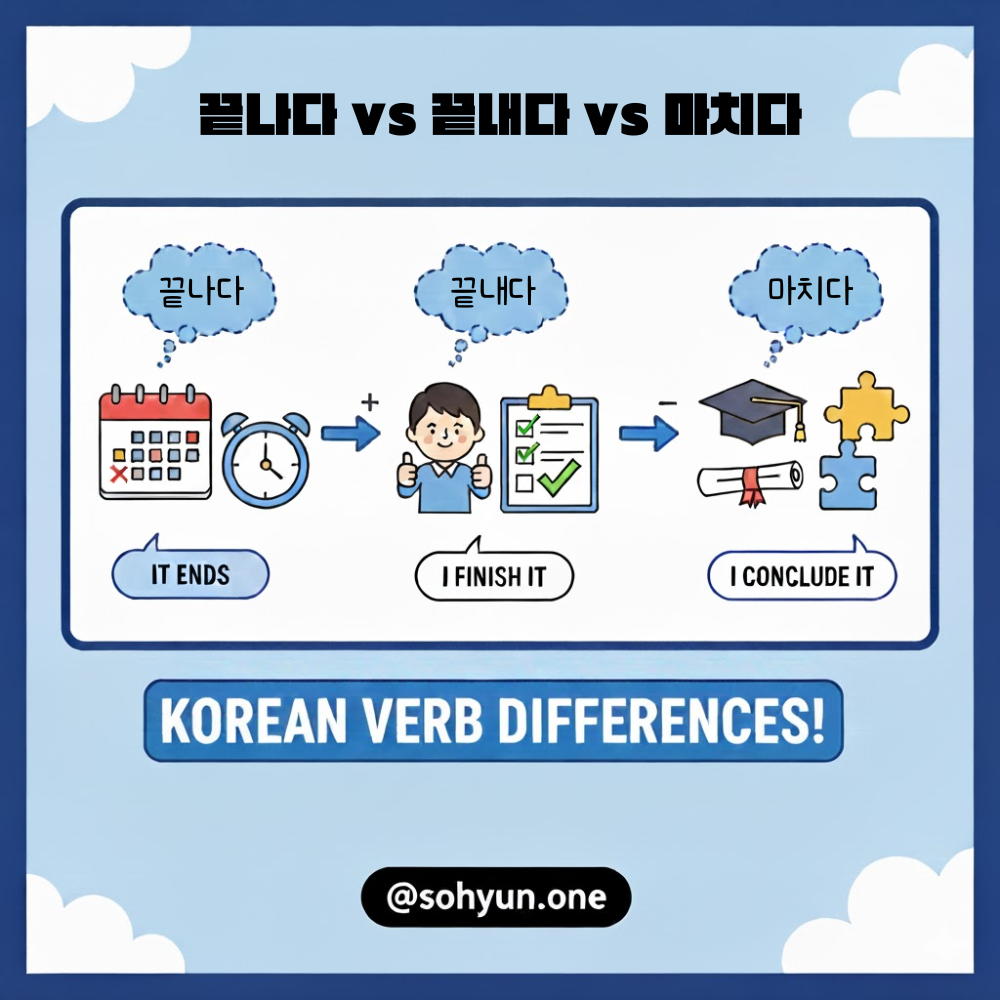

끝나다, 끝내다 and 마치다

Ø How are they different “끝나다, 끝내다 and 마치다”?

🟦 1. 끝나다 — intransitive: “to end / to be over”

The subject ends by itself.

English equivalent: something ends.

✔️ Key idea

The event naturally comes to an end.

Often used for events, shows, classes, meetings, situations, feelings, etc.

✔️ Examples

영화가 끝났어요.

The movie ended.회의가 아직 안 끝났어요.

The meeting is not over yet.방학이 벌써 끝났어?

Is vacation already over?장마가 이제 끝날 것 같아요.

I think the monsoon is about to end.

🟩 2. 끝내다 — transitive: “to finish something”

Someone finishes something.

There must be an agent (a person or group) who does the action.

English equivalent: to finish / complete (something).

✔️ Key idea

It means SUBJECT actively finish something.

Always has an object (what SUBJECT finished).

✔️ Examples

숙제를 다 끝냈어요.

I finished my homework.드라마 정주행을 하루 만에 끝냈어요.

I finished binge-watching the drama in one day.이 프로젝트를 이번 주 안에 끝낼 수 있어요?

Can you finish this project within this week?청소 다 끝냈어?

Did you finish cleaning?결국 일을 제시간에 끝냈다.

I managed to finish the task on time.

🟧 3. 마치다 — “to finish/end (something)”

Transitive, like 끝내다, but slightly more formal and often used for events, processes, official activities.

Also very natural with ~으로/로 마치다 (“to end something with … / to conclude with …”).

✔️ Key idea

Similar to 끝내다, but feels more purposeful and formal/polite.

Often used in speeches, announcements, ceremonies, meetings, schedules.

✔️ Examples

🔹 Basic “finish something”

수업을 일찍 마쳤어요.

I finished class early.오늘 업무는 여기서 마치겠습니다.

We will finish the work here for today. (formal nuance)녹음을 성공적으로 마쳤습니다.

We successfully finished recording.

🔹 ~으로/로 마치다

Used to mean “to end with / to conclude with”.

오늘 수업은 이것으로 마칠게요.

We’ll end today’s class here.회의를 박수로 마쳤어요.

We concluded the meeting with applause.발표는 질의응답 시간으로 마치겠습니다.

I’ll conclude the presentation with a Q&A session.

🟪 4. Quick Comparison Table

Expression

Transitivity

Main Meaning

Typical Use

Example

끝나다

Intransitive

Something ends by itself

Events, shows, natural endings

영화가 끝났어요.

끝내다

Transitive

You finish something

Tasks, homework, projects

숙제를 끝냈어요.

마치다

Transitive

Finish/conclude (often formal)

Classes, meetings, events

회의를 박수로 마쳤어요.

혼란스럽다, 헷갈리다, 혼동하다& 혼동되다, 어리둥절하다, 당황하다 & 착각하다

Ø How are they different “혼란스럽다, 헷갈리다, 혼동하다& 혼동되다, 어리둥절하다, 당황하다 & 착각하다”?

This 6 expressions translated to “confuse, confused, confusing” many times, but there are slightly differently used. Here are some explanations for it. However, in real life, Korean native speakers often confuse how to use them or use them differently, so it would be good to understand when each word is used and try to write accordingly.

1) 혼란스럽다

Meaning:

Used when a situation or someone’s mind feels chaotic, overwhelmed, or disoriented due to too many things happening or too much information. More formal than “헷갈리다.”

Examples

정책이 자주 바뀌어서 주민들이 혼란스러워요.

→ The residents feel overwhelmed because policies keep changing frequently.수능 영어 시험 43번 문제 때문에 학생들이 매우 혼란스러웠다.

→ Students were very confused because of the 43rd question in the Korean SAT English test.경제 상황이 불투명해 시장이 혼란스럽다.

→ The market is in a chaotic state due to unclear economic conditions.

2) 헷갈리다

Meaning:

Casual everyday expression meaning to mix things up, get things wrong, confuse similar items.

It’s about memory mistakes or similarities between things.

Examples

두 고양이가 너무 비슷해서 계속 헷갈려요.

→ The two cats are so similar that I keep mixing them up.오른쪽과 왼쪽을 헷갈려서 길을 잘못 들었어요.

→ I confused right and left and took the wrong turn.캘리포니아 시간대를 헷갈려서 Zoom 회의에 늦었어요.

→ I mixed up the California time zones and ended up being late for the Zoom meeting.

3) 혼동하다/혼동되다

Meaning:

A more formal verb meaning to confuse two concepts, facts, or items.

Used in academic, logical, or official contexts.

혼동하다 = to confuse

혼동되다 = to be confused (passive)

Examples

두 용어를 혼동하면 연구 결과가 왜곡될 수 있다.

→ Confusing the two terms can distort research results.'자유'와 '방종'을 혼동해서는 안 된다.

→ You must not conflate “liberty” and “license”.이 조항은 다른 법과 혼동되기 쉽다.

→ This clause is easily confused with another law.

4) 어리둥절하다

Meaning:

Describes a sudden feeling of bewilderment, puzzlement, or being taken aback by an unexpected event.

More like “blinking in surprise” or “being puzzled and unsure.”

Examples

갑자기 무대 조명 불이 꺼져서 어리둥절했어요.

→ I was bewildered when the stage lights suddenly went out.그의 말에 모든 사람이 어리둥절했어요.

→ Everyone became puzzled by what he said.소현 씨의 고양이 별이가 어리둥절한 표정을 지었어요.

→ Byeol, who is Sohyun’s kitty looked bewildered.

5) 당황하다

Meaning:

To be flustered, embarrassed, panicked, or unsure how to react in a sudden situation.

Includes a social/emotional reaction (blushing, hesitating, freezing).

Examples

공격적인 질문에 당황했어요.

→ I was so flustered by the offensive question.실수를 지적 받아서 당황했어요.

→ I became embarrassed and flustered when my mistake was pointed out.리허설 중에 목소리가 안 나와서 당황했어요.

→ I was flustered because my voice didn't come out during the rehearsal.

6) 착각하다

Meaning:

To mistakenly believe something, due to a wrong assumption or misperception.

Often translates to “I thought ~~ but I was wrong.”

Examples

공연 시간이 오후 6시인 줄 착각해서 서둘렀어요.

→ I wrongly thought the performance time was 6PM so I rushed.그 강아지가 동동인 줄 착각했는데 전혀 다른 강아지였어요.

→ I mistook the puppy for DONGDONG, but he was a completely different puppy.그 소문을 사실로 착각하면 안 돼요.

→ You shouldn’t mistake that rumor for the truth.

🧭 Quick “Which One Should I Use?” Guide

If you want to say…

Use

Why

“There’s too much going on. My brain is overloaded.”

혼란스럽다

Describes chaos and overwhelming situations

“I mixed them up.”

헷갈리다

Everyday mix-ups (names, numbers, roads)

“I confused the concepts.”

혼동하다

Logical / academic confusion

“I froze because I didn’t expect it.”

어리둥절하다

Sudden bewilderment

“I panicked / got flustered.”

당황하다

Emotional reaction,a embarrassment included

“I thought it was A, but it was B.”

착각하다

Wrong assumption or misbelief

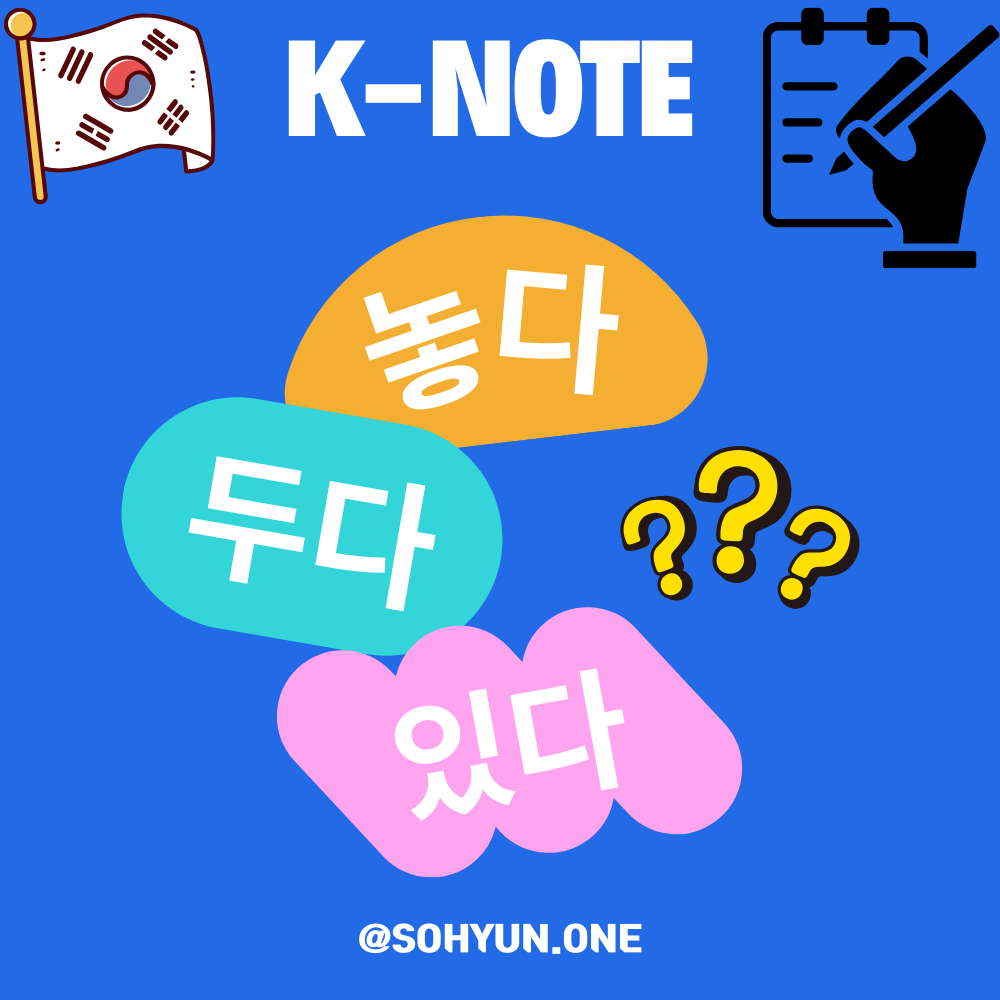

~아 놓다 vs ~아 두다 vs ~아 있다

How are they different “~아/어 놓다, ~아/어 두다, ~고 있다 and ~아/어 있다”?

🔎 1. -아/어 놓다 — “do something on purpose and leave it that way”

This pattern emphasizes that the action was intentionally done, and its resulting state is kept for a reason—convenience, preparation, or habit.

The focus is on purposeful preparation.

✔ English nuance

“I did it (on purpose) and left it like that.”

✔ Examples

❗ Daily life

문을 열어 놓았어요.

I opened the door and left it open on purpose.불을 켜 놓고 잤어요.

I turned the light on and slept with it on.

❗ Preparation

손님이 올 거라서 과자를 미리 사 놓았어요.

I bought snacks beforehand and have them ready because guests are going to come.

❗ Reminder / habit

중요한 문서는 파일에 넣어 두세요.

Put the important documents in a file and leave them there.

🔎 2. -아/어 두다 — “do something and keep it that way for later benefit”

Very similar to -아/어 놓다, but more emphasis on longer-term benefit, preparation, convenience, or preventive action.

Often used in instructions, planning, or when something is done in advance.

✔ English nuance

“I did it and kept it that way for future use or benefit.”

✔ Examples

❗ Preparation for later

환기를 하려고 창문을 열어 두었어요.

I opened the window and kept it open so the room can ventilate.내일 아침에 먹으려고 샌드위치를 만들어 두었어요.

I made Sandwich and kept it for tomorrow morning.

❗ Long-term helpful state

Sohyun.One 비밀번호를 잊지 않게 메모해 두었어요.

I wrote it down so I won’t forget the password of Sohyun.One later.여행 가기 전에 짐을 미리 싸 두었어요.

I packed my bags in advance for the trip.

문서를 백업해 두세요.

Please back up the files and keep them saved.

🔎 3. -고 있다 — “an action is currently in progress”

This expresses an action that is happening right now, ongoing, or repeated in a continuous way.

✔ English nuance

“I am doing this now.” / “This action is happening.”

✔ Examples

❗ Right now

문을 열고 있어요.

I am (in the process of) opening the door.정현 씨가 비빔밥을 먹고 있어요.

Junghyun is eating Bibimbap.멜 씨는 소현 씨를 기다리고 있어요.

Mel is waiting for Sohyun.

❗ Ongoing repeated action

요즘 한국어를 배우고 있어요.

I’m learning Korean these days.

🔎 4. -아/어 있다 — “the result of an action remains”

This expresses a static state that was caused by a past action.

The action itself is already finished; now we focus on the current condition.

✔ English nuance

“It is in the state of being (verb-ed).”

“The action is done, and the result remains.”

✔ Examples

❗ States of objects

문이 열려 있어요.

The door is open (it remains open).불이 켜져 있어요.

The light is on.

❗ Clothing / things worn

모자가 벗겨져 있어요.

His hat is (in the state of being) taken off.창문에 커튼이 쳐져 있어요.

The curtains are drawn on the window.

❗ Situations

한강 다리에 차가 많이 서 있어요.

Cars are (in the state of being) stopped on the Han-river bridge.

📌 Quick Comparison Summary

Pattern

Focus

English meaning

Example

-아/어 놓다

intentional action + leaving it

“did it on purpose and left it like that”

창문을 열어 놓았어요.

-아/어 두다

preparation /

future benefit

“did it and kept it for later advantage”

물을 데워 두었어요.

-고 있다

action in progress

“am doing (right now)”

문을 열고 있어요.

-아/어 있다

resultative state

“is in the state of being (verb-ed)”

문이 열려 있어요.

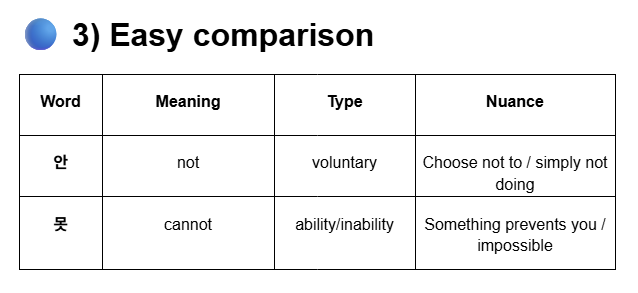

안 vs 못

How are they different “안 and 못”?

🔵 1) 안 — “not” (voluntary negation)

Meaning:

“안” is used when someone chooses not to do something or decides not to.

It expresses intentional, voluntary, or general negation.

Think: “I don’t / I won’t / I’m not doing it (by choice).”

Examples:

마이크는 절에 안 가요. = Mike is not going to a temple. (SUB choose not to)

저는 고수를 안 먹어요. = I don’t eat coriander. (maybe because I don't like it)

숙제를 안 했어요. = I didn’t do my homework. (I didn’t do it—not necessarily impossible)

🔵 2) 못 — “cannot” (inability / impossibility)

Meaning:

“못” expresses inability, lack of capability, external circumstances, or something preventing the action.

The nuance is: “I can’t / I’m unable to / It was impossible.”

Think: “I can’t do it (because something stops me).”

Examples:

시력을 잃은 후, 저는 책을 못 읽어요. = I can't read a book after losing my sight. (I’m unable to)

저는 어제 점심을 못 먹었어요. = I couldn’t eat lunch yesterday. (maybe I was sick or had no time)

저는 오늘 요가 학원에 못 가요. = I can’t go to the Yoga studio today. (because something prevented me)

🔵 4) Same verb, different meaning

✔ 안 가요 = I’m not going.

(Decision / choice)

✔ 못 가요 = I can’t go.

(I’m unable to — busy, sick, no transportation, etc.)

✔ 안 먹었어요 = I didn’t eat.

(I chose not to eat.)

✔ 못 먹었어요 = I couldn’t eat.

(I was sick / had no time / no food available.)

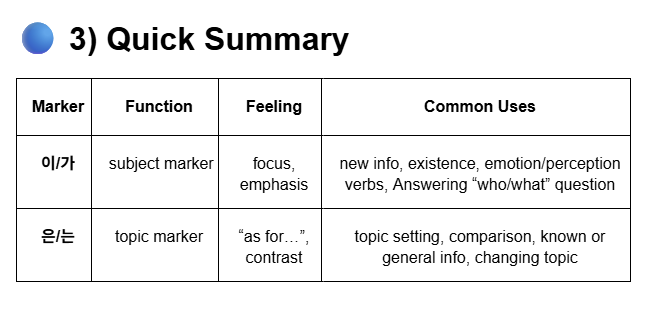

이/가 vs 은/는

How are they different “이/가 and 은/는”?

Before starting the explanation, I declare that, to be honest, it’s difficult to fully understand the difference between **은/는** and **이/가** through grammar explanations alone. You really need to *use* Korean a lot in real life — speaking, reading, and listening — to grasp their nuance clearly. So try to expose yourself to plenty of real Korean—everyday conversations, shows, and other content—to naturally pick up how they’re used.

Then, here are the concepts of 이/가 and 은/는!

🔵 1) 이/가 — Subject Marker

Core Meaning

“이/가” marks the exact subject of the sentence.

It tells us who or what is performing the action or who/what is being described.

When It’s Used

Introducing new information

When something appears in the conversation for the first time.

Focusing on the subject

When the speaker wants to emphasize which person/thing is involved.

With emotion, perception, and existence verbs

verbs like “to be (exist),” “to appear,” “to be seen,” “to like,” “to dislike,” etc. ( the Korean expressions such as 있다/없다, 나타나다, 보이다, 좋다, 싫다 so on )

Answering “who/what” questions

Because it marks the specific subject.

Natural Feeling

Similar to highlighting or pointing:

“THIS (person/thing) is the one that…”

Examples

한국의 대표적인 명절로 설날이 있습니다.

→ There is Seollal, which is a Korean representative holiday. (introducing new info)이 집 칼국수가 정말 맛있어요.

→ The Kalguksu of this restaurant is really delicious. (subject focus)저는 고수가 싫어요.

→ I dislike coriander. (perception focus)누가 회의에 올 거예요? / 제이슨이 회의에 올 거예요.

→ Who will come to the meeting? / Jason is going to come to the meeting. (Answering “who/what” question)

🔵 2) 은/는 — Topic Marker

Core Meaning

“은/는” marks the topic of the sentence — what the sentence is about.

It sets the context or theme for what follows.

When It’s Used

Topic introduction

“As for ___,” “Speaking of ___.”

Contrast or comparison

A vs. B, differences, opposites.

General statements or known information

Background, general truths, facts.

Changing topics

When shifting the conversation direction.

Natural Feeling

Similar to saying:

“As for…” / “Regarding…”

Examples

이 카페는 라떼가 맛있어요.

→ As for this cafe, Latte is delicious. (topic introduction)사과는 좋아하지만 바나나는 싫어요.

→ I like apples, but bananas? I don’t. (contrast)서울은 겨울에 너무 추워요.

→ Seoul is so cold in winter. (general fact)지금까지 한국 음식에 대해 알아보았습니다. 다음은 한국 대중 문화에 대한 이야기입니다.

→ So far, we have learned about Korean foods. The following is the story of Korean pop culture. (changing topic)

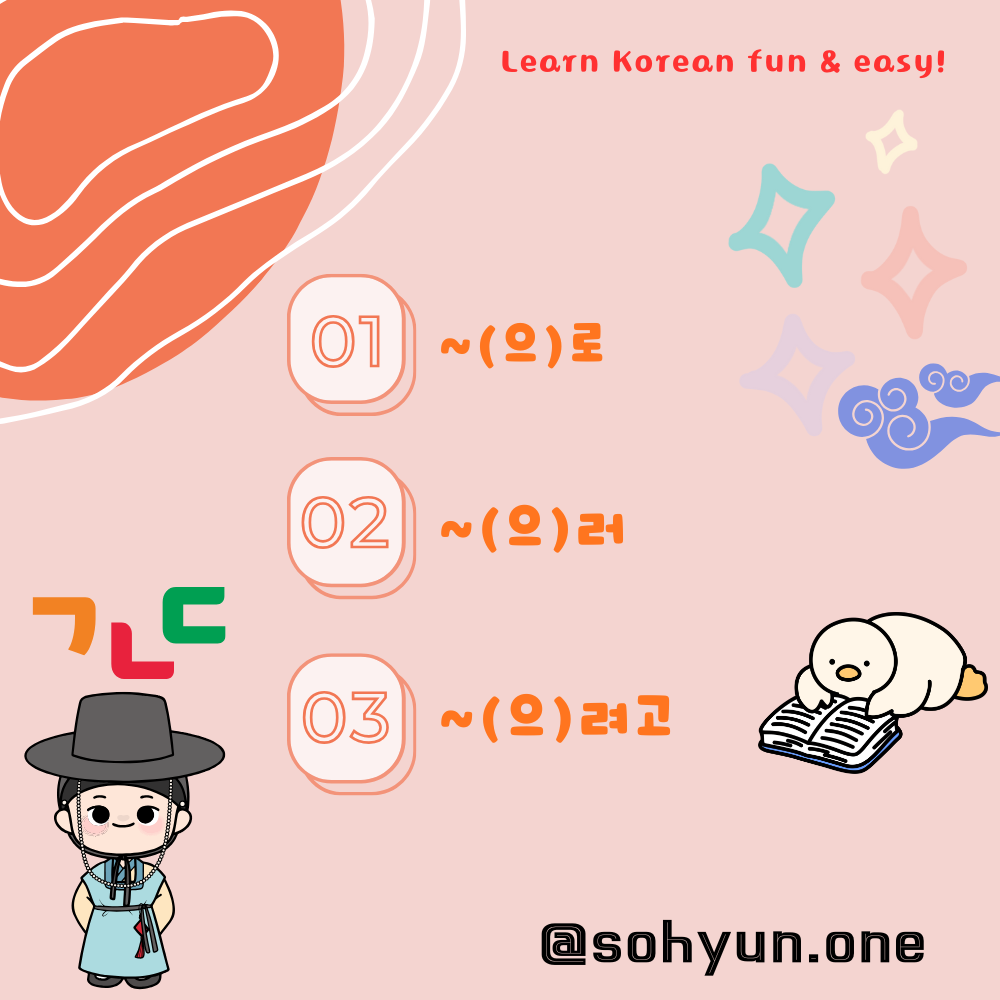

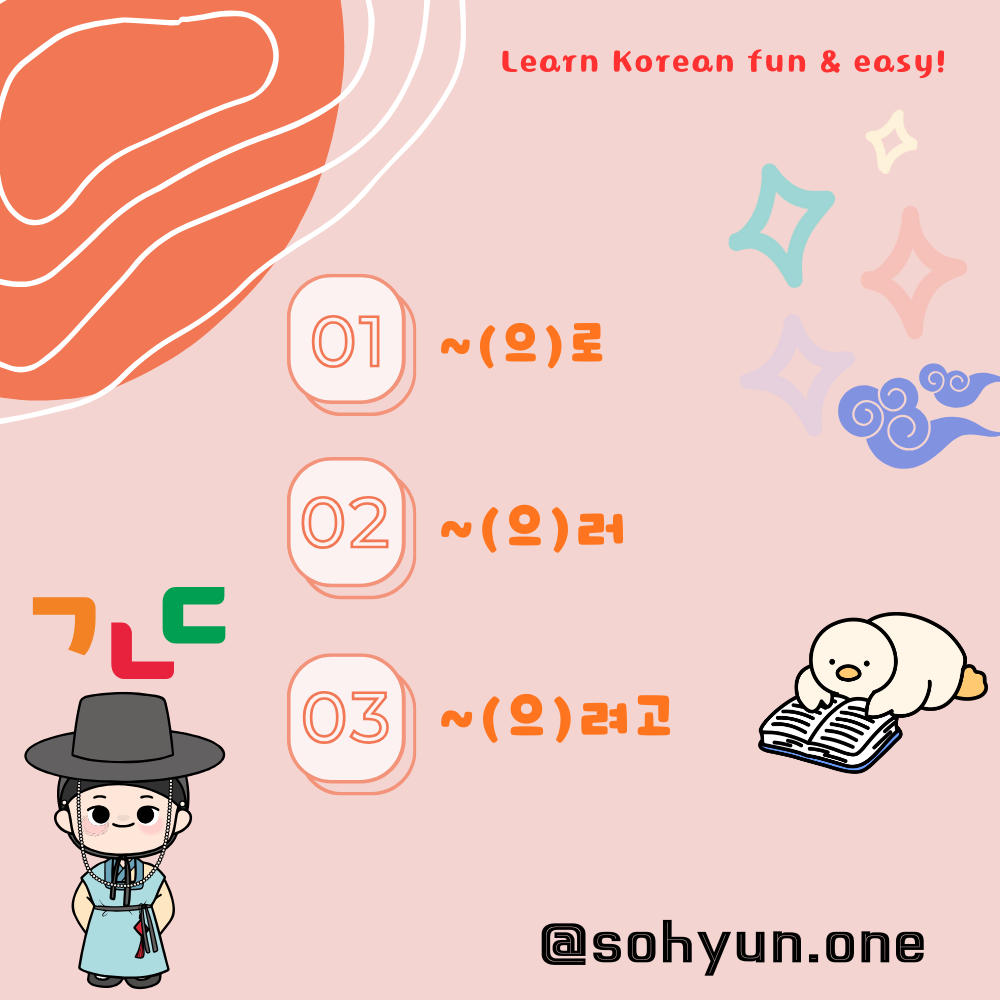

(으)로 vs (으)러 vs (으)려고

How are they different “(으)로, (으)러 and (으)려고”?

📘 1) ~(으)로 [ ~(eu)ro ] — direction, means, method, material, Purpose, or role

Meaning

“~로” mainly indicates where something is headed, how something is done, what materials are used, or what role or purpose something has.

When used to show purpose, it must follow a noun, not a verb.

Form

Noun + 로

- Noun ending in Vowel or ㄹ Batchim + 로

- Noun ending in Batchim except for ㄹ + 으로

Key Uses

Direction: toward a place

Means: by bus, by taxi

Method: in Korean, in English

Material: made of wood, made of silver

Purpose (noun only): for a gift, for lunch

Role: as a nurse, as a contents creator

Examples

내일 집으로 가요. = I go to home tomorrow.

시청까지 지하철로 갈 수 있어요. = You can go to the city hall by subway.

한국어로 말해요. = Let’s speak in Korean.

이 테이블은 나무로 만들었어요. = This table is made of wood.

학생에게 약과를 선물로 줬어요. = I gave my student Yakgua as a gift.

소현 씨는 콘텐츠 크리에이터로 일해요. Sohyun works as a contents creator.

📘 2) ~(으)러 [ ~(eu)reo ] — purpose of movement (only with movement verbs)

Meaning

“~(으)러” expresses the specific action you are going somewhere to do.

It always implies physical movement with a clear purpose.

Form

Verb stem + (으)러

- Verb stem ending in Vowel or ㄹ Batchim + 러

- Verb stem ending in Batchim except for ㄹ + 으러

Only works with movement verbs such as

가다 (to go)

오다 (to come)

다니다 (to frequent)

들어가다 (to go in)

나가다 (to go out)

Restrictions

Cannot be used without a movement verb.

Describes purpose of an action, not intention or planning.

Examples

점심 먹으러 가요. = Let’s go to eat lunch.

지민이는 친구를 만나러 나갔어요 = Jimin went out to meet a friend.

운동하러 헬스장에 가요. = I go to the gym to exercise.

📘 3) ~(으)려고 [ ~(eu)ryeogo ] — intention, plan, or purpose

Meaning

“~려고” expresses a plan, intention, or purpose, whether or not movement is involved.

It has the widest usage among the three.

Form

Verb stem + (으)려고

- Verb stem ending in Vowel or ㄹ batchim + 려고

- Verb stem ending in Batchim except for ㄹ + 으려고

Key Points

Shows intention: SUBJECT intend to…

Shows purpose: in order to…

Can be used for intention, plans, efforts, or goals, not only with physical movement.

Can appear with or without movement verbs.

Examples

저는 책을 많이 읽으려고 노력해요. = I try to read a lot of books.

강아지가 신발을 물려고 해요. = The puppy intends to bite shoes.

닉 씨는 한국어를 배우려고 해요. = Nick is planning to learn Korean.

영화 보려고 극장에 갔어요. = I went to the cinema in order to watch a movie.

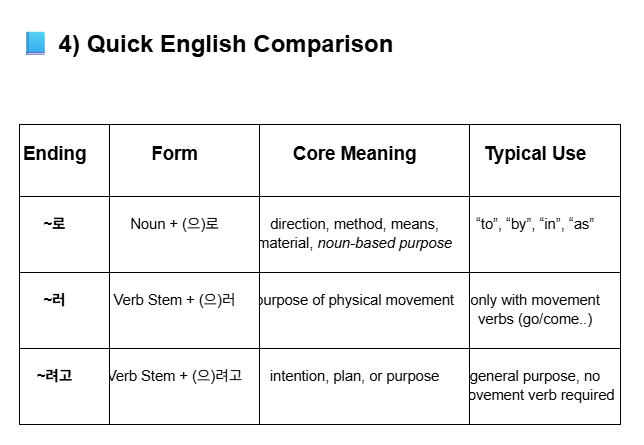

후에 vs 뒤에 vs 다음에

How are they different “후에, 뒤에 and 다음에”?

📌 1) 후에

Grammar type: Dependent noun (의존 명사)

Core meaning: Indicates the passage of time after an event or time point.

Usage note: Works naturally with time nouns, numbers, or specific events.

Examples:

30분 후에 뵙겠습니다! : See you in 30 minutes!

수업 후에 도서관에 갈 거예요. : I’m going to the library after the class.

회의가 끝난 후에 QnA 시간이 있습니다. : There is a QnA session after the meeting.

Key point: Focuses on elapsed time; more formal/neutral than “뒤에.”

📌 2) 뒤에

Grammar type: Noun + particle (명사 + 에)

Core meaning: Originally a spatial noun (“behind”), but extended to mean “after” in time.

Usage note: More casual than “후에”; can refer to near future (“a bit later”).

Examples:

집 뒤에 나무가 있어요. (spatial) : There is a tree behind the house

조금 뒤에 소현이에게 전화할 거야. : I’m gonna call Sohyun later

비가 온 뒤에 무지개가 떴어요. : There was a rainbow after it rained.

Key point: Fundamentally a spatial term, secondarily temporal; less formal than “후에.”

📌 3) 다음에

Grammar type: Noun + particle (명사 + 에)

Core meaning: Emphasizes sequence or the next step, not the amount of time that has passed.

Usage note: Can mean “next time” or “after this step.”

Examples:

아침 먹은 다음에 이를 닦아요. : I brush my tooth after eating breakfast.

다음에 보자! : See you later!

회장님의 축사 다음에 회의를 진행합니다. : The meeting will be held after the chairman's congratulatory speech.

Key point: Indicates order rather than time duration.

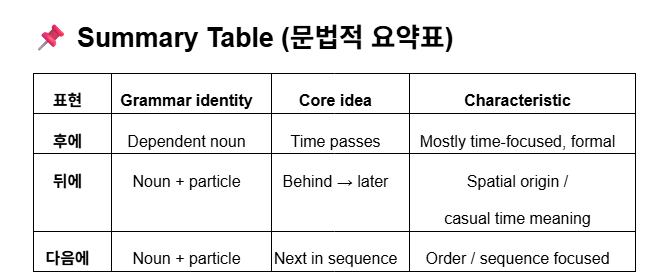

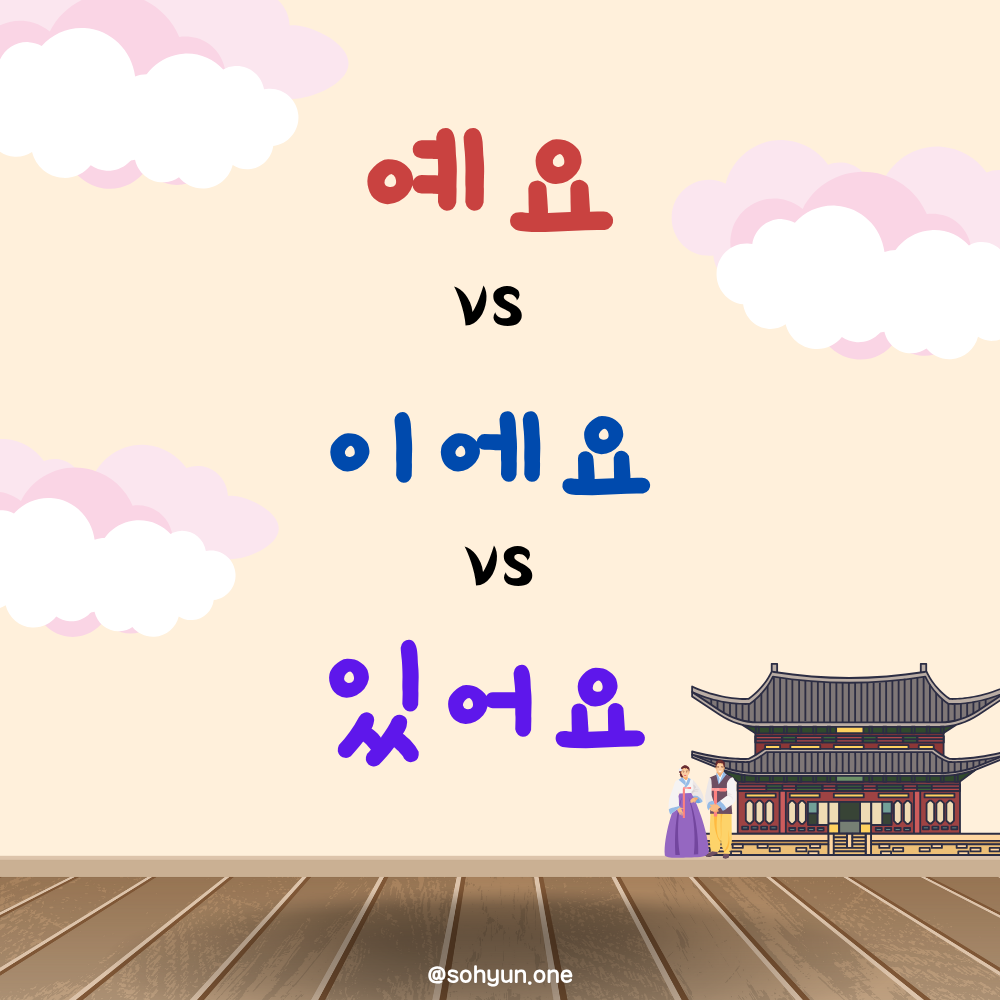

예요 vs 이에요 vs 있어요

These three Korean endings (**예요 / 이에요 / 있어요**) look similar but have **different meanings and grammatical functions**. Let’s break them down clearly 👇

### 🌸 1. **이에요 / 예요 — “to be” (am, is, are)**

These are **copula endings** (like the English verb *to be*).

They attach to **nouns** to say what something *is*.

| Ending | Used After | Example | Meaning |

| ------- | --------------------------- | ------- | ----------------- |

| **이에요** | A **consonant**-ending noun | 학생이에요. | (I) am a student. |

| **예요** | A **vowel**-ending noun | 고양이예요. | (She) is a cat. |

Ending

Used After

Example

Meaning

이에요

Noun ending in Consonant

학생이에요

(I) Am a strudent.

예요

Noun ending in Vowel

고양이예요

(She) is a cat.

🪄 Tip:

* Think of it as “= is/are/am.”

* No space before it — it attaches directly to the noun.

* The choice (이에요 vs. 예요) depends on the **final sound** of the noun.

📘 Example pairs:

* 저는 모델**이에요**. → I’m a model.

* 제 고양이**예요**. → She is my cat.

### 🌼 2. **있어요 — “there is / I have / to exist”**

This is the **verb 있다 (to exist, to have)** in polite form.

It shows *existence* or *possession*, not identification.

Usage

Example

Meaning

To show existence (there is/are)

사람이 있어요!

There is a person!

To show possession (have)

앵무새가 있어요.

(I) Have a parrot.

To show presence [in a certain place]

( SUBJECT am/is/are [in PLACE] )

강아지가 정원에 있어요.

The puppy is in the garden.

🪄 Opposite: **없어요** = there isn’t / I don’t have.

---

### 💡 Summary Chart

Function

Meaning in English

Structure

Example

이에요/ 예요

is / am / are

NOUN+이에요/예요

저는 작가예요.

( I’m a writer. )

있어요

have / there is/are

NOUN+이/가 있어요

책이 있어요.

( There is a book. / I have a book. )

---

### 🔍 Quick Comparison:

* ❌ 저는 작가 **있어요.** → ❌ wrong (mixing grammar)

* ✅ 저는 작가 **예요.** → ✅ I am a writer.

* ✅ 책이 **있어요.** → ✅ I have a book. / There is a book.

달 vs 개월 vs 월

Both of 달 and 개월 are counting noun for months, and 월 is different with those, which expresses each month with sino number - such as 1월 is January, 2월 is February so on. Then, how are 달 and 개월 different?

🌙 1. 달 (dal)

Meaning: A native Korean word meaning “month.”

Usage: Common in casual speech and personal contexts more.

Numbers used: Native Korean numbers (하나, 둘, 셋 → 한 달, 두 달, 세 달).

Tone: Natural, friendly, and conversational.

Examples:

우리 결혼한 지 한 달 안 됐어! → It’s been less than a month since we got married!

한국에 온 지 네 달 됐어요. → It’s been 4 months since I came to Korea.

휴가가 세 달이나 있어요. → I have even three months of vacation.

📅 2. 개월 (gaewol)

Meaning: A Sino-Korean (Chinese-origin) word that also means “month.”

Usage: Used in formal, written, or official contexts more — such as documents, contracts, reports, or news.

Numbers used: Sino-Korean numbers (일, 이, 삼 → 1개월, 2개월, 3개월).

Tone: Formal, objective, and businesslike.

Examples:

계약 기간은 12개월입니다. → The contract period is 12 months.

약정은 24개월이에요. → The subscription term is 24 months.

수강 기간은 6개월 과정입니다. → The course lasts for 6 months.

🪄 Summary

Category

달 (dal)

개월 (gaewol)

Origin

Native Korean

Sino-Korean

Style

Casual, spoken

Formal, written

Numbers used

Native Korean (하나, 둘, 셋)

Sino-Korean (일, 이, 삼)

Common contexts

Daily conversation, diary, letters

Contracts, forms, announcements

Examples

한 달, 두 달

1개월, 2개월

🔍 Example Comparison

“요가 학원에 다섯 달 동안 다녔어요.” → Natural, spoken Korean (I went to the Yoga Academy for five months.)

“이 요가 강좌는 5개월 과정입니다.” → Formal, used in documents (This Yoga lecture is a 5-month course.)

📆 3. 월 (wol) — “Month” (as a unit or name of a month)

1️⃣ Meaning

“월 (wol)” literally means “month” in Sino-Korean (Chinese-origin word).

It is used in order to express each month.

What we have to be careful is to remember 월 IS NOT A COUNTING NOUN!

2️⃣ Usage

“월” is combined with Sino-number, and expresses each month.

Korean

Pronunciation

English

1월

일월 (il-wol)

January

2월

이월 (i-wol)

February

3월

삼월 (sam-wol)

March

...

...

...

12월

십이월 (sip-i-wol)

December

🪄 Example sentences:

제 생일은 5월이에요. → My birthday is in May.

지금은 11월이에요. → It’s November now.